Add your promotional text...

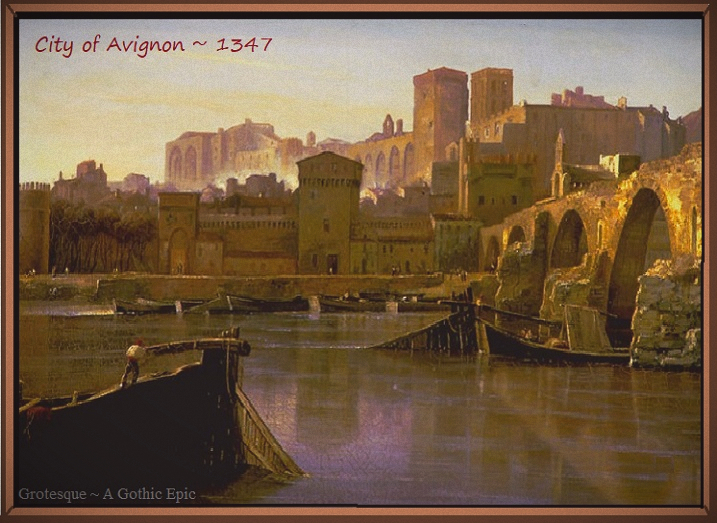

City of Avignon - May, 1347

The afternoon air hung thick with the smell of rain; the western sky lay black. Cardinal Lean arrived in Avignon, from England, blustering into the courtyard of Chateau Mallow in a heavily guarded carriage. Dust churned from the assemblege’s stride only to swallowed up by whirling dust clouds that gathered from an encroaching storm. As the coach neared the entrance, Lean sat forward, peered out of a window, and discovered that some members of his advance guard wandered about dazedly.

Lean’s escort captain spurred his steed forward whilst scolding his shambled guards, "Stand to attention! Stand!" None heeded his command. The captain reigned in his horse and grabbed the nearest one. "Sergeant! What goes on here? Explain this ~ at once! Answer me now!" The sergeant looked up groggily, as though swooning in a drunken state ~ his eyes unfocused, his mouth struggling to form words.

"Enough of this ridiculous charade!" thundered the cardinal. Lean bolted from the carriage, holding a hand on his wide~brimmed hat as he tipped it against the wind. The captain and three other escort guards joined the Cardinal and Lean’s party entered the chateau. Upstairs, the noise of a steady hum intensified as they neared Cardinal Basiliste’s bedchamber. They swept into the room and froze. Several of them moaned and averted their gaze. Cardinal Lean pulled out a handkerchief and covered his nose and mouth as a guard ran to the open window and retched.

Before Lean, a black and bloated Basiliste lay in bed whilst his face entertained a clinging mass of yellow jackets. The insects streamed back and forth through the open window, lugging stung maggots away from the hollows of his head. The dead cardinal was none the more concerned, as he lay rigid and putrid, his eyes drying upon the floor like a pair of dirty coins.

However, Lean was not a man to dote upon such intricacies. He examined the room, his eyes coming to rest upon the parchment leaf lying on the desk, and stepped forward in haste to inspect it. Lean lifted the parchment of the cardinal’s last words, which were addressed to him. Shortly after, the party exited the chateau as hastily as they entered. Lean scanned the letter as he marched. "The Apocrypha! Rush like the wind!" he growled whilst ducking into the coach. "Mount, at once!" the captain bellowed to his guards as he leapt into the saddle. Men hurried for their steeds. The captain spurred his mount to the head of the party. The carriage lurched and catapulted forward. Lean tore his eyes away from the letter and shuddered. With a charging army of twenty~four troops, the cardinal rode west over the Rhone River Bridge, away from Avignon, toward the Apocrypha and toward a monstrous thunderhead swallowing up the horizon. Lean’s attention, however, was consumed with his grave responsibility to the Council of the Apocrypha ~ and to Pope Clement, who remained ignorant of all matters concerning the Council.

With Cardinals Xavier and Basiliste murdered, Lean was the last surviving Upper Councilman. Everything that the Council kept cloistered for nearly five centuries now rested on his shoulder. And though canonical law decreed that the Vicar of Christ ~ the ruling pope ~ was the highest ranking member of the council, Lean knew that it would be difficult, if not impossible, to approach Clement directly. Previously, as a cardinal, Clement had argued fervently against any proposition to which, in his eyes, stood to strengthen the position of the Council of the Apocrypha. Clement had always felt that the Council undermined the authority of the College of Cardinals. Lean entertained no hope that the man had changed his colors after becoming the ruling pope. Nevertheless, he was determined to secure a visitation with Clement even by force, if necessary. And if it came to that, he was prepared to justify such act of insubordination by doing something that had never been done before in the history of the Apocrypha Council ~ by removing the evidence from the archive of the Apocrypha and presenting it directly to Clement in person.

Lean and Clement were opposites in their character; they clashed. Both knew it. Lean was a man of few words: modest, apprehensive, and sincere. Clement was tactless and impatient, enjoying the luxury and social lifestyle; as pontiff, his demeanor was more that of the debonair monarch than the austere messenger of God. When conversations between them did occur, they were formal, brief, and largely uneventful. In the four years since the advent of Clement’s ascension, Cardinal Basiliste had approached the pontiff repeatedly regarding matters of the Apocrypha. Each time, he had been refused an audience on the grounds that, other, more urgent matters demanded Clement’s immediate attention, such as new palace construction, affairs of state, finances and taxation. Clement had neglected to appoint new members to the Upper Council, even after the death of Cardinal Basiliste, and his inaction had caused the once~powerful body to wane, on his part almost certainly deliberate neglectfulness. Yet, Lean now had little choice but to force himself on Clement and remind him of his responsibility to the age~old body of the Council of the Apocrypha.

The Council’s Apocrypha Archive had been constructed in 1334 by order of Pope Benedict XII, who, despite voicing aspirations to return the papacy to Rome, removed all papal records from the Vatican to the new stronghold in France. The tomblike building lay in the vast, damp valley of the Rhone, surrounded on three sides by steep ravines that lay shrouded in second~growth woods and thorny brush. To the East, the ramparts of Avignon towered over the river valley gorge, yet just to the west, the grandeur of the city dwindled ~ along with its stench.

Less than an hour elapsed before the heavily guarded coach, bearing the seal of the Church of Rome, labored up a steep, rutted path, screened by tall stands of evergreens. The stone battlements that rose darkly beyond the trees had an equal shade of black as the sky behind them. The sky thickened as floating ash; the winds reversed and turned to ice. Flashes; thunder ~ in only moments, fat raindrops paved a way for torrential rains. Lean’s entourage struggled up the narrow mudslide of a road, with several dismounted and mud~caked guards pressing against the back of the carriage in combined effort to urge it forward. They heaved it out of puddles; onward, inch by inch, foot by foot. Lightning illuminated the road ahead whilst outlining the ever~looming silhouette of the Apocrypha.

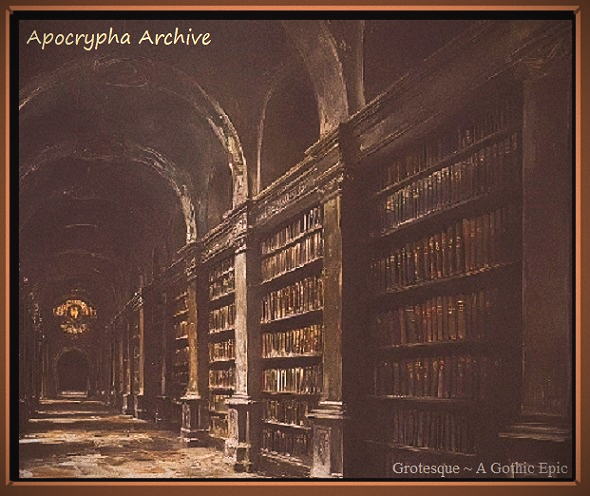

No window interrupted the stony exterior of the imposing block fortress. Its single entrance was attended, day and night, by watches of Council guards, men hand~picked by the Upper Council for their strength of body and will, and unwavering loyalty. Even the rigid protocol of King Philip’s Royal Guard was lacking by comparison. Within those guarded walls lay words of scripture known but to few living men ~ from the complete once~scriptural books of Enoch, Jubilees, Giants, Solomon and others, to ancient scrolls written in tongues not heard on earth in a thousand years. And from artifacts of the long~destroyed Grecian Library of Alexandria to Assyrian clay cylinders that detailed the years following the Great Flood and confiscated from Jewish temples in the earliest crusades, the Apocrypha’s archives held all the existing secrets of the Church, and held it close.

Lean sought material that lay contained in four specific bindings ~ texts that the cardinal knew nearly by memory. And though it was against his better judgment to remove anything from the Apocrypha, he could fathom no better approach to the task that lay before him: to convince Clement of things that no sane man would dare believe to be truth.

The first of the four bindings was the Statue Physique, the largest of them. It contained detailed descriptions of the Council monasteries and their two gatestones. It also contained the history of each. The first gatestone was unearthed in 876, during the reign of Pope John VIII. Located in the mountanous regions of Umbria, within the fellow Papal States of Italy, the excavation site was also home to an ancient Samnite settlement. The second gatestone was discovered in 877, under Pope Stephen VI. Found in current Augergne Province, in France, the monolith sat atop a stony hill, south of the Loire River.

The second of the books was the Council Proclamations. It listed the historical membership of the Apocrypha Council. It listed every pontiff and councilman ever to serve the Upper and Lower Councils. It also contained the Council’s bylaws.

The third binding was the Reformation Exclusions, scribed by Pope Benedict XII in 1336. These were special amendments or exclusionary clauses to the papal bull: the Redemptor Noster. It allowed the Apocrypha Council to govern its two monasteries in ways that it saw fit.

The fourth and last of the texts sought by Lean was the Naramsin Translations. These frail bound pages dated back three centuries and were collectively named, after their author, Naramsin, a recorded Gardiens cleric who, through dedicated service, had managed single~handedly to decipher the French monolith. The translations represented a Latin rendering of the strange language carved upon the faces of the French stone. And since the etchings on the Italian stone were identical, the Naramsin papers served as translation for both gatestones, located in France and Italy.

Lean knew that any of the four texts might serve to awaken the unconcerned pontiff to the real danger at hand, yet it would take all four to bring the man under Lean’s ~ thus under the Apocrypha’s ~ control. He must be made to see, if the Council is to survive. Lean’s carriage came to a halt and he peered out of its portal to see silhouettes in a driving rain as they gathered in two ranks to flank a pair of massive iron~strapped doors ~ the entrance to the Apocrypha.

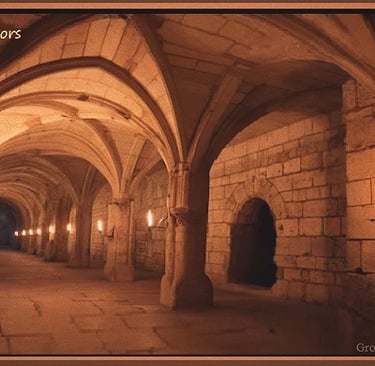

Within the Apocrypha and behind its great doors, wall torches illuminated a score of resolute guards that lined the corridor entrance. On the other side of it, spear butts pounded against the door, followed by a muffled command, "Open, by command of His Eminence, Cardinal Lean of the Apocrypha Council!"

Two guards removed iron bars and strained themselves to open the doors. Cardinal Lean and his Captain bustled through, drenched completely from the heavy rain. The guards bowed as the two passed. The doors closed with a resounding thud. Never breaking stride, Lean and the Captain disappeared into the dim hall, leaving a trail of water that dripped from their garments upon paved stones, which mirrored quivering reflections of the torch flames of the corridor.

As Lean stepped a corner and neared the last of a hallway, six guards abruptly made their presence known. They stood before a tall richly ornate door covered with intricate carvings, embossed with shimmering metal plating, and studded with precious stones. In Greek letters, the word, APOCRYPHOS, lay inscribed above its keystone. The door sergeant stepped forward, hand raised and with his palm outward. "Halt!" The guards behind him raised weapons in kind, and a clattering of heavy iron armor traveled through the hall. Lean halted before the Sergeant, who continued thus: "State the nature of ~"

Lean swiped his hand aside briskly. "I have no time!" He leaned forth, cupped his hand, and whispered the words of passage into the ear of the sergeant.

The soldier spun, clicked his heels, and addressed his door guards, "Give way to His Eminence, Cardinal Lean of the Council!"

The guards quickly parted and the sergeant slipped a large brass key into the lock. They heaved open the tall door and Lean took a torch handed by one of the guards before ducking through the doorway. The heavy and towering door slammed shut behind him with a loud clang. A silence enveloped him there, in the still darkness, only disturbed by his own breath and a steady blowing sound of the torch flame.

Lean moved through the blackness in quick stride, lighting an array of wall torches. The massive room took form as the Cardinal whisked away the darkness. Numerous rows of book casings lined the walls. Aisle upon aisle of them crisscrossed the floors, their shelves harboring a vast assortment of texts - manuscripts, scrolls, and inscribed clay cylinders - all secrets of the Holy See. Lean secured the torch in an empty torch bracket mounted against the side of a shelf. A spacious reading table illuminated before him. He lifted one of several wooden stools around the table and scurried down the many shelf rows. He turned a corner and froze; ice and dread in his veins. Several yards further, before him a stepping stool already stood. He dropped the stool that he carried and ran to the other one.

Lean climbed atop the new stool and searched the shelves, scanning feverishly before he found it - the Statue Physique. With a sigh and an apparent second wind, he retrieved the massive book and hurried to the reading table. No sooner had he dropped it on the table, settled himself into a chair, and cracked open the cover; his heart leapt into his throat. Some of the pages were missing.

"No!" he gasped whilst flipping the pages, hand over his mouth, eyes wide and glistening with a mixture of astonishment and deep terror. Nearly half of the pages were gone - torn out. "No. No! No!" He bolted from the table and ran for the closed door.

"Open this door at once!" Lean cried, pounding his fist against it. A key clicked in the lock and he pushed open the heavy door, surged with newfound strength.

"Who has been in the archive?" Lean screamed.

The sergeant stammered, "Your, uhm - only - only Cardinals of the Council have been admitted."

Lean leaned into his face and growled, "I am the last of the Council. The last! There is no other!"

"What of Cardinal Masson," the soldier asked.

Lean jolted back, his face fell horribly crumpled. "Masson? There is no such Cardinal."

"He ~ this Masson knew the words of passage, Your Eminence! My orders are to allow -"

"The key, give it to me!" Lean interrupted. The solder obeyed. Lean stuffed the key beneath his robe. "I know your orders, guard!" Lean collected himself. "Tell me, what did he look like? Was he dressed" - Lean pointed to his own scarlet robes - "as a Cardinal?"

"Yes, Your Eminence. He claimed to be a newly elected Council member. He told that he had been sent by His Holiness to inspect Apocrypha records. And he knew you quite well."

"Sergeant, my reason for visiting the Apocrypha is to inform His Holiness of his obligations to it. How might he issue orders regarding things of which he knows nothing?"

"Your Eminence, my orders are -"

"Mother of God," Lean mumbled, distracted beneath trembling fingers, eyes pacing over the floor before locking back with the sergeant’s and narrowing, "What did he look like, this Cardinal Masson?" he pressed.

"Was quite certain of himself - carried himself like a Cardinal. Your height - blond hair - fair skin - ah - and one brown eye and another, white! The soldier pointed to his left eye. "This one was blind."

Lean hardened and ground his teeth. There was only one cardinal with such eyes.

Damn him, Lean thought. Blasi - the College must have put him up to it.

"Who came with him - the escort?" Lean demanded of the bewildered sergeant.

"He came alone, Your Eminence - on his own mount."

"On his own?" Lean huffed loudly. "Sergeant, I come with tens of guards and an armored carriage. Did you not think it odd that a Cardinal might travel outside the palace, and out of the city, unescorted? On a steed, at that?"

"Your Eminence, each time he came, this Masson - I mean this man whispered to me exactly the words you yourself used moments ago. Else, I would have not allowed him inside. My orders -"

"I know your orders!" Lean erupted. "‘Each time he came,’ you said - how many times, sergeant? How many times did you open these doors to this intruder?"

"Many in recent days," the sergeant said lowly. "I expect him again on the morrow; shall I take him into custody, Your Eminence?"

Lean knew that without Clement’s knowledge of the Apocrypha, Blasi’s arrest might only serve to anger him and inflame an already fragile situation.

"No, sergeant," Lean replied calmly. "Simply refuse him access to the Apocrypha. Do not arrest him. The new Council shall decide what to do with him." Then another thought came to him. "Have you ever repeated the words of passage to anyone?"

"Me, Your Eminence? I have not. I am forbidden by order to do so."

"Never? Even to yourself?"

"Never, Your Eminence."

The man had stood guard over the same door for nearly two decades. Lean had no reason not to believe him. Then it opened in his mind; as he saw the key turn in the lock and a door to a sinister truth open, he saw it at once. Cardinal Basiliste was tortured into confessing the words of passage; this assuredly connected Blasi with Basiliste’s murder.

"You shall say nothing of this, to anyone. We shall change the words of passage before I leave. No one crosses the threshold of the archive - not one, save me. Do you gather me?"

"Indeed, Your Eminence. I do," the sergeant hastily agreed.

"One thing more: Did the intruder come or go with anything - even, a sliver of paper?"

The sergeant answered, "On the first day he removed two bindings from the archive and I insisted he return them. I angered him, yet he complied. Since then, he has carried nothing away in his hands. I inspected his robe to the best of my abilities, yet I dared not demand a search of his person, since he was - I gathered him a Council Cardinal," the man burst out. Cheeks flaming, he eyed the floor stones as he murmured, "Exactly as I did you, Your Eminence."

Lean frowned. "Speak no more of this. Close the door."

"Yes, Your Eminence." The sergeant heaved the tall door closed and Lean withdrew the key from his vestments, locking the door from inside. He returned to the reading table.

Lean assessed the damage, gathering what Blasi might have learned from the torn pages. He flipped through more pages.

"Damn!" Lean pounded his hand on a missing section. He searched deeper in the book only to find all of Naramsin’s translations removed.

"Damn him!" He slammed his fist on the table; his anger resounded through the shelf, the floor, and perhaps to even the very core of the earth. Through Clement, Lean would see to it that Blasi kept silent.

"CAW! CAW!" There came a raspy call, "CAW!" A startled Lean jolted his head up to find a fluttering raven perched atop a bookshelf, whipping the air with its wings. Lean rose slowly. "How in the -" The bird lunged at Lean, aiming squarely for his eyes. With a shriek, the cardinal stumbled back. As lightening, the screeching black feathers tore open his face with its flashing beak and talons. In a mask of blood and blinded, Lean scrambled backward, crashed into a massive shelf and fell down. The shelf rocked back and the raven took flight. On his knees and clearing his eyes of blood, Lean discovered the bird perched calmly atop the shelf where he first saw it. Slowly, he rose to his feet.

"Creak!" Lean looked over his shoulder to see the rocking bookcase falling back toward him. He held his arm out and screamed. An avalanche of books and shelving - the mountain came down on him as a landslide of bindings, rattling the room even to the tall door. The torch, mounted against the side of the shelf, crashed atop the heap of books and set them ablaze. Then all fell quiet - all but a crackling flame and the muffled moan of a cardinal pinned beneath the rubble. At once, the form of the raven burst into a cloud of dissipating smoke and vanished.

"Your Eminence!" The sergeant called to him, beating against the tall door.

Beneath the case, Lean lay bound with broken legs and shattered ribs. Books and shelving blocked him on every side. Smoke crept through the heap. "Dear God! Help me! Guards!" He cried.

The smoke rolled along the surface of the floor and, beneath the threshold of the door, it gathered around the sergeant’s boots. "Fetch a ram! Summon every soldier! Now," The sergeant bellowed to his men. They scattered. He pounded against the door, "Cardinal Lean! Open the door!"

Time passed and the smoke thickened. When the soldiers returned with their ram, they pounded against the tall door, doing so with stinging tears and to the choking screams of a Cardinal burning feet-first.

~*~

It so happened, that fate had been kind to Cardinal Blasi. Had Lean lived but one day more, Blasi would have been accused of murder. The Pope would have had little choice but to begin a thorough investigation of the Apocrypha. And an investigation would have revealed the secret that the Council guarded, and the Pope would surely have appointed a new Upper Council body, even whilst Blasi rotted in a pauper’s grave. Instead, Blasi now found his way magically cleared of obstacles.

On the day after flames engulfed the Apocrypha, the pontiff’s Lord-at-Arms, Captain Pitro, was dispatched to investigate the accident. Pitro returned with his findings: Cardinal Lean’s death and the consuming fire, which destroyed the contents of the archive, was a mere accident. The matter was dropped and the Papacy continued its investigation of Basiliste’s murder, though it was not considered a priority. With King Philip’s scheduled visit to the Popes’ Palace less than two months away - ‘twas politics that occupied the minds and tongues of the palace. The Apocrypha and its secrets would have to wait. After all, England had occupied parts of French soil and Philip needed Pope Clement’s help, under the current truce, to reclaim the lost territories of the North.

Over the course of the following month, Blasi had ample enough opportunity to mull over the records he had stolen. Of keen interest to him were the Naramsin Translations. In the privacy of Chateau Rouge, he read and reread the fascinating text.

If these things are real, he thought, awestruck, then my brother’s specter spoke true: this monolith has the power not only to drive Edward from France, but to crush him, and all of England with him.

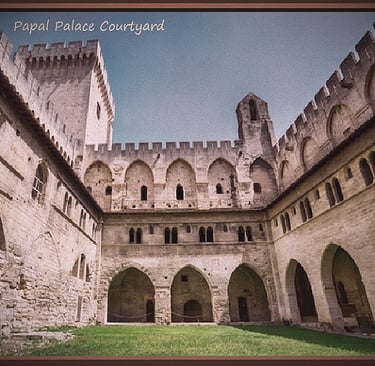

‘Twas early afternoon when Blasi stepped into the cloister courtyard of the papal palace. He spotted Julin walking across the grounds, leading two servant boys. Upon the boys’ shoulders stretched a long bolt of midnight-blue cloth studded with silver buttons.

"Cardinal Julin! A moment of your time," Blasi shouted across the gallery. As he neared Julin, another red robe, Cardinal Firmus, converged. Firmus was also a palace overseer and his duties made him the most intensely disliked of all the Palace Cardinals. He investigated, documented, and reported all palace affairs directly to the Pope. In short, Firmus was the Pope’s eyes and ears, and carried himself as if he had already been elected as the next Pope. However, in truth, his was no more than a self-consumed nosey body.

"Julin, do you know the whereabouts of Cardinal Toussain?" Blasi asked.

Firmus interrupted, "Blasi, have you marked the three wine barrels for His Majesty, King Philip?"

"I did, yestermorn," Blasi answered curtly before turning back to Julin, repeating; "Where is Toussain?"

Julin glanced over his shoulder. "He was following us only a moment ago. Perhaps he - ah! There he comes, now."

Toussain stepped through the archway of the Cloister Gallery with both arms supporting a thick square of folded blue cloth.

Firmus thrust his face between the cardinals, demanding Blasi’s attention. "Has Toussain filled His Majesty’s bottle crates and marked them?"

Julin intercepted this query. "He has. Two eves prior."

Toussain reached the group, out of breath and countenance. "Julin, they shall drop the cloth and soil it if you stand about much longer," he snapped. Julin noticed the three grimacing boy servants, their feet shifting beneath considerable weight.

"Oh, dear! Do not drop it! To the Banquet Hall!" Julin harped to his servant boys. He turned about and acknowledged the two Cardinals. "Blasi; Firmus." He sped away, the boys trailing him.

"I am only just behind you," Toussain called after him. He nodded to Blasi and Firmus, clearly making ready to hurry after Julin. Firmus stepped in front of him, crossing his hands behind him and rocking back on his heels. "His Holiness has requested me to confirm that the bottle crates are packed and marked," he said importantly, staring down his long nose at Toussain. "I expect they are?"

"As they should be," Toussain snapped back.

Blasi grunted, exasperated, "Only a moment ago, Julin admitted that Toussain has readied the bottles." Firmus tilted his head back even further, squinting down at Blasi as from some great height. "Indeed he has, yet I wish to hear Toussain’s words and not those of another. Oh, and, tell me, Blasi, have you placed a guard beside the wine barrels that you marked for His Majesty?"

"There was no need," Blasi said, the corner of his mouth upturned with a small grin. "I informed the wine kegs that if they attempt to escape the cellar, I shall personally see to it that they be drunk to death. Thus, they agreed not to escape."

Toussain choked back a laugh, nearly losing his proper composure.

Firmus’ brow hardened. "I shall pretend that I did not hear the jesting of cardinals," he said coldly. "Blasi, perhaps you have forgotten that England and France are at war. Perhaps you shall take personal responsibility, if His Majesty fall poisoned and die." Turning to Toussain, he continued, "The Lord-at-Arms is not in the Guard Room. Have you seen him this day?"

Blasi broke in. "Perhaps you have already discovered my wine barrels unguarded and have since sought out Captain Pitro to place a guard on them, yes? If so, then it might seem quite pointless of you to ask me if I had placed a guard." Firmus blustered; however, Blasi gave him no opening. "Yet you did ask, perhaps because you intend to convince His Holiness that you have caught me in some horrible dereliction of duty? Might this be the design of your scheme, Firmus? To place yourself in a favorable light with the Holy See by shedding a poor light on me?"

Firmus countered the accusation with a quote from the Book of Proverbs: "A fool uttereth all his mind: but a wise man keepeth it in till afterwards."

Toussain diplomatically disarmed the conflict by answering Firmus’ earlier question. "The Comte de Pointers has since arrived and is in the Dignitaries’ Wing. I believe you may find Captain Pitro there as well, Cardinal Firmus."

"Yes, of course," Firmus agreed, eager to end the exchange with his own words. He nodded carefully to Toussain and Blasi. "Cardinal Toussain; Cardinal Blasi."

Blasi allowed the man enough space to regain some of his equilibrium before calling after him, "And he that passeth by, and meddleth with strife belonging not to him, is like one that taketh a dog by the ears."

Firmus stiffened visibly, taken to heart as his own quote from the Book of Proverbs, yet continued walking as though he had not heard.

Toussain bit his lip to conceal a creeping laugh. He leaned toward Blasi, whispering, "Captain Pitro is there, behind you." He gestured subtly toward the arches at the far side of the courtyard. "There, behind the furthest column. He speaks with a guard."

"Ah, well done, Toussain." Blasi strolled over to the column. He found Pitro behind it and whispered in his ear. Pitro nodded to Blasi’s whisperings and then barked an order to the guard, who turned and hurried off in the direction of the Great Cellar. Blasi patted Pitro’s shoulder in gratitude and returned to Toussain.

"My friend, we must speak. There are matters of grave importance I must share with you," Blasi urged, almost pleading. Toussain observed the other man’s nearly obsessing stare, with the twisting of the hands and eager posture. Looking past Blasi’s shoulder, he barked, "Boy! Come in haste!" A big-eared squire boy approached the scarlet-clad cardinals warily. "Your Em-nuh-ness?"

"Eminence, boy," Toussain corrected him. "Emm-ih-nence. You are one of Cardinal Julin’s boys, yes?"

"Yes, Your - yes, sir."

"Your master is in the Banquet Hall." Toussain offered the square of heavy silk to the scruffy child. "Now take this cloth to him. Tell Cardinal Julin that Cardinal Toussain shall be there shortly. And if you soil this cloth, squire, you shall answer for it. Do you gather me?"

"Yes, Your Em-nuh-ness."

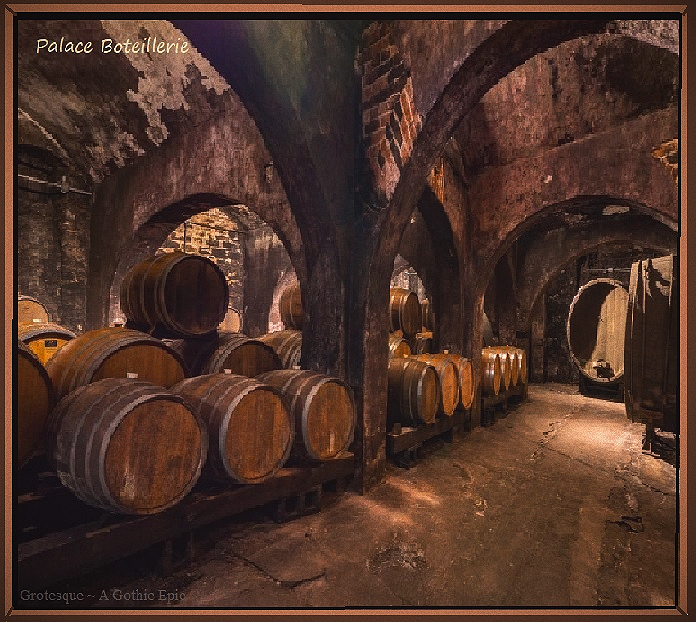

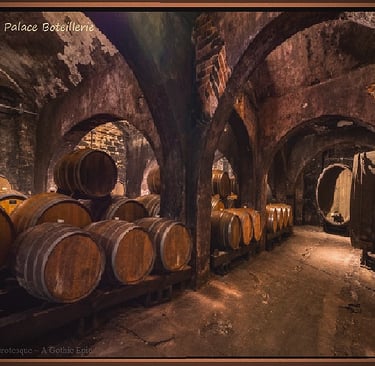

Toussain handed over the material with a sigh. "Go on, then. Be off." The boy rushed away with the cloth. Toussain said speculatively, "Not the Cellar. You sent a guard in there. And I have servants in the Pantry. The Boteillerie Room?"

"Good enough," Blasi replied. They left the courtyard together.

The two red robes whispered together, walking onto rough wooden stairs into the Boteillerie. Toussain inspected the six rooms for servants before motioning Blasi into the Bottle Storehouse, where they traded through a maze of full and empty racks until they came to a rear corner of the room. Here, they stood with clear advantage, as they were capable of spotting the approach of someone walking in on them, and long before the intruder might hear their hushed exchange of words.

Blasi spoke for long moments whilst a stew of warring emotions passed across Toussain’s features: shock, skepticism, horror, distaste, and, finally, open disbelief.

"How can you expect me to believe something so absurd?" he requested stoutly, after Blasi had finished. "Like some fantastic tale!"

Blasi defended himself, "Have you ever seen the two monasteries I speak of, written in the papal tax records? Have you ever known of the purpose of the Council of the Apocrypha? Better still, what it holds in its archive? Do you know why the Council and its cardinals have always been separate from the church electorate? Toussain, I have seen records from the Apocrypha. What I tell you is truth, before God and France. They are guarding the very gates of hell."

"So, you might have me believe," Toussain said slowly, "that the Council of the Apocrypha built these monasteries to guard stones which are, in truth, the gates of Hell? I am to believe that if one speaks these inscriptions carved upon the stone, one might open Hell itself. And these gatestones" - Toussain’s lips lingered around the word as though it had a noxious taste in his mouth - "shall save all of France? Blasi, do you gather me a palace cardinal, over the years, so respected by my peers, because I lack reason?" He huffed. "Even an imbecile would be hard-pressed to believe such a reckless claim as yours!"

"‘Tis truth! I know it is difficult to grasp, Toussain - I swear, it is truth."

"Very well." Toussain made his mouth into a grim line. "Let us suppose that you do speak the truth. Let us also suppose, Blasi, that you might find means to penetrate either of the Council’s monasteries. That you find this guarded stone and speak the words which might open the gates of hell." Toussain looked pointedly at Blasi. "Supposing as much, how then shall you persuade its demons to do your bidding? What shall you say, when these - spawns of Satan spew forth from this stone? ‘Go forth, destroy the English?’" Toussain uttered a harsh, nearly shrieking laugh. "Inasmuch as a bird freed from a cage does not return on command, why must these spirits obey you once free? Moreover, how can you open and close a stone with words? No, Blasi; you speak as but a child, overcome with excitement!"

"There is much more to the gatestones than opening and closing them," Blasi countered. "They are similar to gates, yet they neither open nor close. Spirits can pass through them. The translations are in verse form, like Scripture. ‘Tis by these words, the words on the stones, that one can summon spirits from them - or return them."

Toussain shook his head. "You have yet to answer my question. Why must these spirits do your bidding once you have freed them?"

"The translations confirm that one can summon spirits from these gatestones and command them!" Blasi was nearly frantic in his desperate insistence, pounding a fist against the thick plank of the Bottle Room wall. "And there is more. I had a blessed vision not long ago. My brother, Jean-Jacques, who was slain by the English at Crecy, came to me. He spoke of -"

"Enough of this foolishness!" Cardinal Toussain blurted. "I am required in the Banquet Hall. Perhaps you can summon the spirit of your brother and these - your stone demons to help you. Neither Julin nor I shall stand by you when an inquisition accuses you of heresy, Blasi. Oh, you can be assured that I shall carry your wild tale to Julin, as you have asked - and you can be certain that he shall gather you thoroughly mad with fever. As, do I." Toussain turned away.

"No - wait. A moment more," Blasi called after him.

Toussain did not halt or turn as he spoke. "I have never had this conversation with you, and if you claim I have -"

"Would you care to see the records for yourself?" Blasi made his way around the racks of bottles. "I have them."

Toussain stopped abruptly and rubbed his chin. No College Cardinal would refuse the opportunity to peer the Council’s records, regardless of Blasi’s senseless claims, if he truly was given access to whatever it was the Council had guarded so jealously, for so long.

"Show me these records, then. Let me see for myself, and gather my own truths. If they are convincing, I shall hear more of it. If not, I shall return the records to you - on the condition that you cease to trouble Julin and me with this madness. You shall forget that you have ever spoken to us about the matter. Do I have your word on it, Blasi?"

"Indeed, you do. And do I have yours, that you shall guard these records at every cost, and return every leaf after your private inspection?"

"I have no need for them. I shall return all."

"Very well then." Blasi seemed almost to fall limp in his relief. He would have allies, once his friends see what he had seen. "And when you discover that I speak the truth, I shall expect an apology from you."

"It would serve as much," Toussain laughed, yet contemplatively. How ridiculous this man was in his madness. Nevertheless, the records of the Apocrypha -

"‘Tis agreed."

"I shall have the records for you at first light. I shall bring them to the Cellar." Blasi departed.

Toussain watched Blasi cross the courtyard, waiting before leaving the Boteillerie. After all, the man may have already spoken this insanity to others - it would not do well to be seen in the company of one who, Toussain was sure, would end up on the Inquisitor’s rack before a fortnight had passed.

As agreed, Blasi was waiting in the Cellar the following morning. He gave Toussain the Apocrypha pages, which he had torn out of the Statue Physique and various other bindings - nearly a hundred pages in all. It took Toussain only a few hours of spellbound reading to realize, with dawning horror, that Blasi spoke the truth. ‘All true,’ he thought, dazed, ‘All of it.’ For the remainder of the day, he sat in his study, not moving, not eating, or drinking; the ancient writings scattered about him. As darkness fell, he staggered to his feet as though struggling awake through the fog of a nightmare. "All true," he whispered to the empty room. Gathering the pages carefully, Toussain went in search of Cardinal Julin.

City of Avignon - Pope's Palace - June 1347

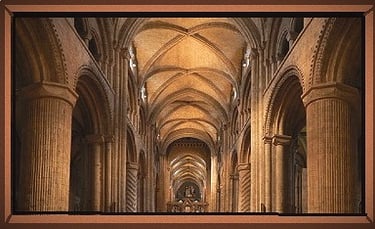

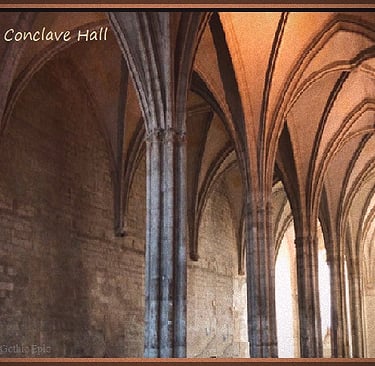

The Conclave Hall of the Popes’ Palace stood lined with murals of religious scenes and paintings of papal dignitaries. Flemish wall tapestries hung high over the lavish accommodations. The Hall stretched long and wide beneath towering walls. Its floor spread like an ocean beneath the massive timbers of the ceiling. The arched beams of the roof resembled the inverted hull of a ship, perhaps fit for even Noah’s odyssey. The hall served as the Palace guestroom - a suite for visiting dignitaries and was suitable for any King.

Guards and servants poured in and out of the Hall entrance, unpacking King Philip’s luggage. "Make way!" a voice bellowed from outside the door. The entryway cleared as guards bearing halberds marched in, escorting a fat Cardinal through and to the far end of the Conclave Hall. They passed through the entrance and into an elaborately decorated Banquet Hall before stopping short.

A large dining table centered the room. Alone and seated in a high-backed posted chair commanding the table, King Philip enjoyed lamb. He dined alone. Before him, the table lay covered with gold and silver dishes. At his elbow, there stood a valet, ever ready to refill his wine goblet.

One of the guards struck his halberd against the floor and addressed the Hall; "Cardinal Julin of the Holy See seeks an audience with His Majesty, King Philip of France."

"See him in," Philip barked, coughing through a mouthful of meat.

The guards allowed Cardinal Julin to continue forth and they turned and marched out of the Hall. Then the two fell away and froze into position beside the interior of the entryway. Julin approached the table, and bowed. "Your Majesty."

Philip looked up, carelessly wiping his greasy chin, "As always, Cardinal, your kitchens rival mine - the service - incomparable. Have you considered my offer - to head my kitchens and banquet hall, Julin? I shall reward you twice and again all that you now have. I would expect no more than what you do now, for His Holiness."

Julin smiled and bowed again. "I am most honored, Your Majesty, yet my service must remain with the Church." Philip shook his head in disappointment.

"Well." Philip pointed to a silver tray. "It seems you have confounded my valet even, this time Julin. What is it?" On the tray rested two miniature oil lamps, a porcelain apparatus with three legs, and a tin of water. In the center, a silk-lined box sat, finely worked with paintings of dragons, and housing a makeshift nest of straw with a single egg.

"May I?" Julin asked.

"Indeed you may," Philip assented, staring at the painted dragons.

Julin assembled the pieces. "‘Twas acquired from a Genoese trade ship. I gathered you might enjoy it." He slipped the two lamps and the tin into position. Next, he retrieved the egg and slipped it into the contraption. "The lamps need lighting."

"Bring a flame," Philip snapped his fingers. The valet left and returned with a flame.

Julin lit the lamps. "The oils in the lamps are special. Now, the egg is prepared whilst you eat and may be eaten after your meal." A flame heated the tin of water beneath the egg. Another burned behind the egg, before a concave reflection plate. The focused light offered a view into the egg.

Philip peered within to discover the darker yolk of the egg suspending in an opaque glow. "I must have one. What is the name of this three-legged contraption?"

"Call it what you wish. ‘Tis yours, Your Majesty," Julin smiled, reaching in front of the valet to refill Philip’s goblet. "May I have a word alone with you?"

Philip waved off the valet and opened his hand toward a chair. "Sit, Julin. Speak." Julin squeezed himself into the chair.

"Egg window," Philip mumbled suddenly with a grin.

"Your Majesty?"

"The name of it -" Philip gestured to the dragon-decorated tripod. "’Tis an egg window - since I can see within it."

"Egg Window - indeed, an excellent name." Julin cleared his throat. "Your Majesty, If I may - I gather that you came to seek the advice of His Holiness regarding Edward and - the most unfortunate happenings at Crecy."

"Then someone has misled you," Philip stated, turning cold and distant. "Advice is like water - everywhere and always changing. Advice, I have. Paris is full of it. I need armies."

"May I be more direct with you, Your Majesty," Julin leaned forward and whispered, catching a glimpse of the door guards as he spoke.

"Guards! Leave us!" Philip called out. The soldiers stepped out of the great hall and disappeared behind closed doors. He leaned back and listened as Julin spoke of the Apocrypha’s Gardiens gatestone and its potential use as a weapon against the English. Julin explained how the King might help, by lending him enough soldiers to gain control of the gatestone.

"Thus, as you may now gather," Julin stated, summing his explanation, "the situation is most dire and your assistance is critical."

"Oh indeed! Of course; of course," Philip stated, swallowing the last chews of meat. Philip bowed his head, grabbed a napkin, and slapped it over his mouth. Choking gasps followed. The king’s face flushed red.

Julin rose from his seat. "Your - Your Majesty?" Julin grabbed a goblet of water from the table.

Philip dropped the napkin, flung back his head, and burst into laughter, the hall echoing with his hilarity. Between chuckles he coughed, "Spirits - legions of ghosts? Yes, I shall destroy him with my ghosts. Indeed! With my trusted ghosts!" Philip cast his eyes toward the ceiling and bellowed with melodramatic sarcasm, "Be gone, Edward, or I shall summon my ghosts upon you!"

Julin set down the goblet and fell back in his chair, deflated. "Your Majesty, I am in earnest."

Philip’s face fell stern. He leaned forward on one elbow, glaring as he whispered, "As am I! I have already raised an army of ghosts, Julin - at Crecy. Bring them back. Bring back my armies. Allow them to avenge their deaths on Edward. Can your stone weave such magic?"

Julin attempted further explanation. "The gatestone - ‘tis a machine of sorts, yet -"

Philip folded his arms on the table and interrupted him, "And, suppose you can release these ghosts of yours. What, then? How shall you ask them to destroy Edward? Tell me, Julin, how do ghosts slay? Perhaps they shall frighten Edward to death?" He slammed his fist onto the table. Julin jolted and leaned back. "Foolishness! I need warm bodies - men trained in battle! I need weapons. I need monies. If I wished to frighten Edward, I would send him a fleet of my finest ships brimming with the rotting heads of all the Frenchmen he slew!" Philip’s eyes were icy daggers and Julin dropped his gaze.

Philip collected himself and leaned back in his chair. "Unfortunately, Cardinal, my convictions are not as - how might I say it - as refined as yours. I see battles won by blood, sweat, and well-supplied armies - not by ghosts. I did not come to Avignon for advice, or prayer, or promise - or tales of magical stones. As I am well aware, the Holy See collects taxes from both France and England. France needs those monies for her continued defense and I have come in the name of France - as her serving king."

"Your Majesty, with only a few of your men, I believe -"

"No, Cardinal; here is what I believe. I believe His Holiness has put you up to this. I believe His Holiness does not wish to extend me the loan and has sent you to give me yet another promise - only, this time, a damned army of ghosts." Philip lifted the egg from the contraption, sat back, and began peeling it. "Inform Clement that his little ruse has failed."

Julin leapt from his chair. "No! His Holiness did not send me! He is ignorant off all I told you! And he must remain so!"

Philip froze, his eyes burning into the trembling Cardinal.

Julin found his seat awkwardly and bowed his head. "Forgive me, Your Holiness. I am a witless fool."

Philip returned to peeling his egg. "There is more about you that even I suspected. Consider this, Julin; I shall agree to lend some of my troops to your ridiculous cause if His Holiness extends me the loan equal to the taxes collected from France and England. If His Holiness refuses, then perhaps everyone may come to learn how His Holiness hides this - this heretical stone of his."

"But, Your Majesty! You must not speak of this -"

"I MUST - not be told what not to do, Cardinal," Philip countered resolutely. He leaned across the table and whispered, "Ensure my loan and you get your soldiers. That is the agreement. Now, I must rest." "Your Majesty -"

"Enough, Julin. We never spoke." Philip turned and shouted across the hall, "Valet, I am finished! Guards, enter!" The guards reappeared. "See the good Cardinal out! And clear my quarters! No more visitors this eve!"

"Yes, Your Majesty." Julin arose, bowed, and glumly followed the guards to the door.

~*~

The following day, Philip and Clement and their fleet of notaries convened in the Treasury Hall. Only then did Clement realize that Philip’s loan request was of a substantial size - substantial enough to slow the construction of the Popes’ Palace. Rumor spread; whispers carried through the corridors. The meetings were not going well and most papal officials knew well enough now to leave the irate pontiff undisturbed. Most were also certain that Clement would offer Philip little more than a portion, a promise, and a prayer. Angry and afraid, Julin approached Toussain, who, then spoke to Blasi with equal concern. If Clement discovered their intentions, he would have all three expelled from the College, excommunicated, and thrown into prison. Blasi quieted their fears and went to work, weaving a web involving what seemed to be an impossible task.

At midday, Blasi entered the Guard Hall, approached a guard, and whispered in his ear. The guard replied with several nods and Blasi slipped him a letter and a gold coin.

"Not a word of it to anyone. Now be ready, he comes," Blasi commanded with narrowing eyes.

"Yes, your Eminence," the guard bowed as Blasi sped away. In a moment, arriving from the Dignitaries Wing, Cardinal Firmus entered the Guard Hall. As instructed, the guard approached Firmus and presented him with the letter.

"Your Eminence," the guard bowed.

"Yes, what is it," Firmus huffed.

"I found this leaf on the courtyard grounds. It does not appear to be the orders of a guard. Perhaps it is important?"

Firmus read the letter, pursed his lips, and searched the guard’s eyes.

"Can you read?"

"No, your Eminence."

Then how do you know it is not a guard’s orders," Firmus questioned him.

The guard replied defensively. "I know the look of such orders; most all appear the same. This leaf has no noble mark on it.

"Did you show this leaf to anyone?"

"I only recently found it. You are the first to see it."

"Good, then I shall see it returned. You are not to discuss this leaf with anyone. You never found it. Do you gather what I mean, soldier?"

"I do."

"If I hear word of it, I shall personally come for you - now back to your duties."

"Yes, Your Eminence," the guard bowed and walked away. Firmus looked about, greed and guilt in his eye; he clutched the letter close to his chest and read it again:

These are His Majesty's conditions: He shall grant in secret one tenth of the loan to the Cardinal who convinces His Holiness to extend the full amount. If the loan shall be greater than his initial request, His Majesty also agrees that the Cardinal is due one tenth of all excesses. Burn this leaf. Speak to none.

Firmus searched the hallways for prying eyes. Seeing none, he slipped the letter beneath his robe and sped away, unaware of Blasi watching him in the shadows from afar.

Within the hour, Firmus stood in the Four-Windowed Room of the palace, convincing Clement to extend an even larger loan than Philip requested, suggesting higher and more frequent reimbursements. The discussion grew heated. Rarely had Firmus seen Clement so angry. However, Clement frequently relied on Firmus’ advice in stately affairs. As it happened, the Pope reluctantly agreed to Cardinal Firmus’ suggestions.

That eve, King Philip and Pope Clement signed the documents. Out of the transaction, Philip envisioned the severed head of Edward, Firmus saw himself on the papal throne, and Blasi remembered his dead brothers’ faces. Toussain and Julin saw themselves as Cardinals of France, whilst Clement foresaw more delays in the creation of his massive papal machine. The transaction pleased all ~ everyone but Clement, his treasurers, and the Papal Chamberlain.

The following morning, King Philip summoned Cardinal Julin to the Conclave Hall. Philip was in the posted chair with Cardinal Firmus already before him, hands clasped, as Julin was announced. The Cardinals exchanged glances. Both were was as curious as to the business of the other, yet neither dared speak openly with the other present.

"Ah. Cardinal Julin, come," Philip waved him to come forward.

Julin bowed. "Your Majesty."

Philip turned to Firmus. "You were saying, Cardinal Firmus?"

Firmus cleared his throat. "I came to see if you required anything, Your Majesty."

"His Holiness sends a Cardinal to see after the needs of his royal guests? I have brought my own fleet of servants. To what do I deserve such special treatment?" Philip rubbed his chin.

"Not exactly, Your Majesty." Firmus cleared his throat and stole a glance at Julin. "If it pleases Your Majesty, might I have a word with you - alone."

"Indeed. Cardinal Julin, please wait without. Cardinal Firmus, come closer." Julin bowed and left the hall.

Firmus whispered, "Your Majesty. ‘Twas me - I secured your loan. I came to discuss the compensation."

Philip chuckled. "I see that the Church is not without its own corruption. Very well, Cardinal, I am due three kegs of wine in the Palace Cellar. I shall leave one with you - we shall call it a gift, of course."

Firmus squirmed. "I can not accept it, Your Majesty. If I may, I wish to speak about the tenth of the loan."

Philip was stunned. "The tenth? A tenth of the loan - as compensation?"

"The tenth, Your Majesty, for convincing His Holiness to grant the loan."

Philip scowled. "You can have what I offer you, Cardinal. Even that is more than adequate. Now, do you wish the wine?"

"His Holiness shall never allow it. Your Majesty, I have the leaf describing the terms of our agreement." Firmus slipped the page from his robe and Philip read it. He raised his brow.

"What nonsense is this? Who scribed this about me?"

"Are you not aware of it, Your Majesty?"

"I said no such thing! And as for compensation, it shall be my silence in this matter!" Philip slipped the paper into his vest. "If you tell anyone that you or Cardinal Julin approached me, expecting a portion of the loan for yourselves, I shall inform His Holiness that both of you conspired against him. Leave me before I reconsider my silence!"

"Yes, Your Majesty." His face set, Firmus bowed and left the room. Once outside, he glanced at Julin and scowled before escaping hastily down the hallway.

"See Cardinal Julin in," the king ordered. The guards complied.

Philip took the paper from his vest as Julin approached and fanned it slowly between two fingers. He stared at Julin, and Julin stared at the paper that he knew was Blasi’s note. Philip roared with laughter and returned the leaf to his vest.

"You are very resourceful, Julin. Be at ease; all is well," Philip chuckled. "I merely persuaded you to ensure my loan - and you did it well. You may forget my placing you in jeopardy with His Holiness." He laughed again. "I knew His Holiness never sent you. I know you too well. Ah - and the Cardinal Firmus believes you have also come for your reward. I made it known that, if either of you confess anything about it, I shall share the matter with His Holiness."

"My most humble appreciations, Your Majesty." Julin bowed, smiling.

"Now, as to your magical stone of ghosts, I shall grant you soldiers only under strict terms. Firstly, His Holiness is to know nothing of it - ever. Secondly, my men are in your service for a number of days only."

"Very well, Your Majesty," Julin replied.

"You shall have my Captain Bourne and his men. I trust him in matters of secrecy. He only, is to know the full concern. Speak not to his men; he shall command them."

"Of course, Your Majesty."

"He is now in Avignon and has two hundred men. That shall suffice, yes?"

Julin shook his head, "Indeed not. Too many."

"Bourne keeps his soldiers together. He is the finest of my Royal Guard and I see no need troubling him with separating his men. The offer stands at two hundred or none. Which is it?"

"Two hundred, Your Majesty." Julin sighed.

"Done. Now share with me the very details. When and where shall they meet you, and what do you require of them?"

Grotesque ~ A Gothic Epic © is legally and formally registered with the United States Copyright Office under title ©#TXu~1~008~517. All rights reserved 2026 by G. E. Graven. Website design and domain name owner: Susan Kelleher. Name not for resale or transfer. Strictly a humanitarian collaborative project. Although no profits are generated, current copyright prohibits duplication and redistribution. Grotesque, A Gothic Epic © is not public domain; however it is freely accessable through GothicNovel.Org (GNOrg). Access is granted only through this website for worldwide audience enjoyment. No rights available for publishing, distribution, AI representation, purchase, or transfer.