Add your promotional text...

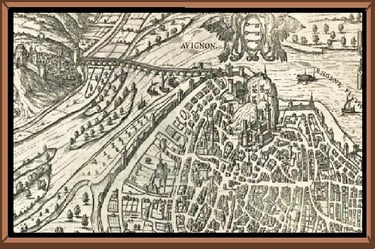

City of Avignon, France ~ 1342

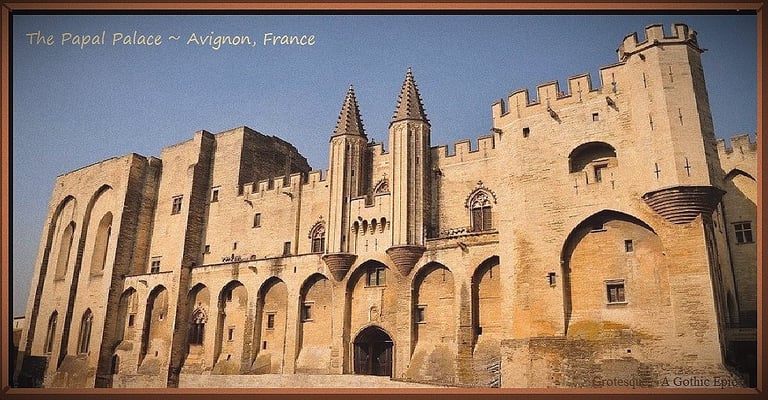

'Twas now fourteenth century Europe and Avignon was the very heart of the Christian Empire. Situated on the banks of the Rhone River, Avignon was the Babylon of the West ~ the city teemed with tradesmen and soothsayers, drunkards and craftsmen, soldiers and ambassadors, Jezebels and thieves. High ramparts encircled the town, intended to protect it from outside invasion. With so many people pressed together within its walls, adequate sewage disposal proved a daunting task and a foul odor hung over the enclosed congestion like an invisible but quite tangible pall.

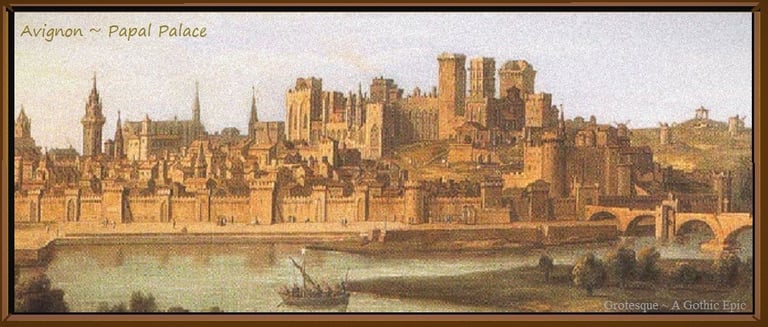

Rising out of that sea of stench, the Palais des Papes (Popes’ Palace) towered over the land. Built upon a rock cast aside by the Roman Empire, the looming configuration served as the cornerstone and pontifical throne of the Holy See. The enormous Gothic castle stood as the largest in existence. It was a massive dragon~like fortress: fortified walls twelve feet thick ~ complete with battlements, towers, and arrow loops. The whole of the formation sprawled as a double palace, boasting twin quadrangles. In its wings: massive halls, the larger and more significant of them being the consistory, conclave, banquet, and treasury halls. In its bowels: a great cellar, housing seemingly countless gallons of wine extracted from rolling acres of papal vineyards and aged in ranks of immense wooden casks. In its heart: hellish hearths, circulating tens of thousands of bread loaves a day and nourishing Avignon’s Babylonian hoard. The Popes’ Palace was nothing short of a medieval monster scaled to magnificent proportions ~ the beast stood colossal.

Within the palace were the squirming entrails of corruption, wealth, seated iniquity, power, and great authority, ceaselessly rolling and contracting. Invariably, the castle corridors teamed with Cardinals and Curia officials, papal guards and squires, councilmen and lawmen, concubines with lowly gazes, knights and their lords, visiting dignitaries and their escorts, including distinguished relatives and private entertainers of the Pontiff.

During the reign of Pope Benedict XII, twenty~four cardinals served in the College of Cardinals. Of the College, Cardinal Blasi was its fiery wolf, disliked by most of the mainstay. One of the youngest cardinals, Jean~Francois Blasi, was a man of good health, standing tall and sporting a head of blonde hair. His most notable feature, disturbing enough, lay in his eyes ~ together, a clear brown eye and a blind milky eye worthy of a devil’s return gaze. Only a few of the cardinals tolerated his company outside formal engagements. Yet for Blasi, a few was all that he required ~ those Cardinals with enough inner~circle influence to serve his needs. Mostly, they were Senior Cardinals who also served within the Popes’ Palace as overseers.

‘Twas standard practice in Avignon for cardinals of higher stature to be assigned the overseeing of various wings, halls, chapels, and grounds of the palace. For years, Blasi was the overseer of the Great Cellar. The expansive hold was a subterranean hallway, dug in 1337 and spanning the entire length of the wing housing the Conclave Hall above it. This enormous underground vault held hundreds upon hundreds of seasoned kegs aging some of the finest wines in Europe. Blasi was responsible for nearly every aspect of their production, grape to keg, including the subsequent storage and safekeeping of the wines. Generally considered as an appointment of grand importance; the winery was responsible for a good portion of the annual revenue of the Papacy.

Thus, about the palace, most considered Blasi to be the ‘Cardinal of the Wines.’ Moreover, every connoisseur knew that befriending Blasi was to befriend the Great Cellar. The wiry and gristlish Cardinal Raulin Toussain, overseer of the Palace Pantry and Boteillerie (the Bottle Storehouse), and the very obese yet delicate Cardinal Lilo Julin, master of the Kitchens and Banquet Hall, were two who considered themselves epicures and each had made certain to cultivate the friendship of the Cardinal of the Wines. Blasi knew well enough why these two courted him, yet there was nevertheless amongst them, at the least, an obvious brand of camaraderie.

Unlike the much larger College of Cardinals, the Council of the Apocrypha contained only three cardinals ~ Cardinals Hadour Xavier, Senior councilman; Avit Basiliste, the eldest and most frail, and Edmard Lean, the youngest and most recently appointed of the body. Cardinal Xavier’s service ended with the discovery of his nude and decapitated corpse. A peasant boy discovered his remains in a thicket alongside a road west of Avignon. Scattered in the brush about him lay the remains of his guards, their bodies equally defiled. His murder remained an enigma. Before the rumors of the murders grew stale, Pope Benedict died as well. Though several cardinals insisted that Benedict had been poisoned, and that the string of murders were somehow part of a larger political conspiracy, such speculations were never substantiated. Blasi was closest to the papal wines ~ and a tyrant to boot ~ many suspected him for the poisoning, yet none were bold enough ever to confront him for his fiery temper.

Less than two weeks after Benedict’s state funeral, the French~dominated Conclave hastily elected another Frenchman, Pierre Roger de Beaufort, who was fifth in succession to the Avignon Papacy. De Beaufort was christened Clement VI. Most of the usual dignitaries were present for the election: the College and Council cardinals, the Secretary General, the Vicar General and Vice~regent, chief papal officers of the Kingdom of Naples, the more distinguished Bishops and all the bevy of hangers~on such an assemblage required. An envoy from Philip VI de Valois, king of France, was notably absent, having arrived too late to attend the ceremony.

The power of this election rested overtly with the College of Cardinals. However, only few living men knew that the true power of pontifical persuasion lay in the hands of merely a few ~ namely the Council of the Apocrypha. Over the centuries, the College of Cardinals had evolved its role into an electing body of the Church, now serving the Holy See in much the manner as any parliamentary organ serves its overall organization. In contrast, the Council of the Apocrypha was a small, veiled and purposefully unrecorded papal body wielding an authority that easily rivaled that of the College, the cardinals of the Apocrypha suffered no dominion, save that of God, and were accountable only to His chosen representative on earth ~ the Holy Father and Pope.

The Apocrypha was composed of two distinct levels ~ the Upper and Lower Councils. The Upper Council consisted of the Pope and the Cardinals whom he appointed ~ who, in turn, supervised the abbots and monks of the Lower Council. Since the time of its inception, membership of this Council had varied between sixty and sixty~six members, each appointed by the Upper Council. Appointments to the Council were for life; new members were given charge only upon death of an existing appointee. The two of the original three cardinals of the Upper Council ~ Basiliste and Lean ~ resided in Avignon, in a villa called Chateau Rouge. However, the members of the Lower Council were divided evenly between two equal and remote monasteries in the hinterlands of France and Italy. These were the Abbaye des Gardiens, located in the hills of Auvergne Province, of France, and the Monastero del Cancello, situated in the mountains of Italy’s Papal States, in Umbria.

The Gardiens Abbey of the Lower Council fell under the direction of its resident Abbot Vonig, whilst the Cancello Monastery in Italy fell under the direction of its resident Abbot Domingus. Both Lower Council Abbots reported only to the Upper Council cardinals, who, in turn, reported in secret and solely to the Pope. These isolated monasteries considered themselves Benedictine, yet were not governed in accordance with Benedictine Monastic Rule. They had derived an order unto themselves, which was neither Benedictine, nor Franciscan, nor Cistercian. For centuries, these monasteries had remained disjoined from the monastic rule and fell under the exclusive control of the Council of the Apocrypha. The Council and its two monasteries, with its esteemed circle of servants, were outwardly a kind of ‘holy ghost,’ which guarded the most ghastly skeleton of the Papal Closet. However, few secrets escaped Lucifael ~ those of the Council, in particular.

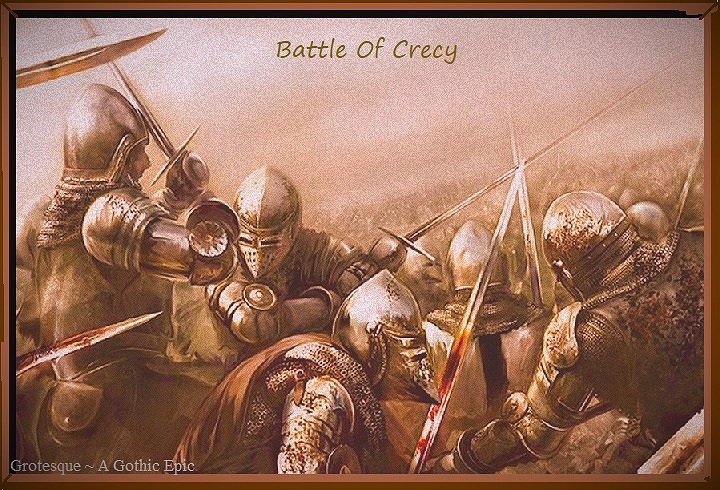

Thus, whilst Lucifael decimated Asia with her breath~of~death; she stood equally occupied with Europe, deceiving two of it’s nations. Through marriage, France and England crossed royal bloodlines. In short, a king died and England had rightful claim to France ~ the devil lay in the details. Nevertheless, the entangled kingdoms found themselves at an impasse and the bell tolled. And from such, came the ringing in of the Hundred Year Wars. The very first of these battles, one, which would prove to be the most horrific in history; played itself out on French soil and would forever be called the bloody Battle of Crecy. Many would bear witness to the horrors that came to happen on the muggy August afternoon of the battle.

Crecy~en~Ponthieu ~ Northern France ~ August, 1346

Only remnants of the storm remained. Thunder rolled off to the West, and lightning lanced into the distant hills. A luminous black raven settled amongst the wind~warped branches of a splay oak, disturbing a few battered leaves. Its black pupils swelled and contracted, cold and mechanical, as if some machine governed the pitch eye. The raven rocked its head and cawed at the retreating thunderhead twice, and then again. Below the oak perch, a column of French soldiers sloshed along a muddy, rutted road.

The Frenchmen ~ most of them peasants whose hands were more accustomed to wielding axes and pitchforks rather than swords ~ were marching to war through the sodden hills of northern France. Their newly crowned king, Philip VI, had told that English dog, Edward III, that France would never share the throne with England, or anyone else, for that matter. France, Philip decreed, was sovereign, and its throne was only his. Responding to Philip’s cavalier claim with a fit of rage, and thenceforth determined to unseat him, Edward carved a path through France, burning entire villages in its wake. He was intent on inflicting enough injury to force Philip’s downfall ~ within his own ranks. When news reached Philip of Edward’s brazen attack, he gathered many of the French lords to march against the invading intruder.

Philip’s call to arms was so great that Edward, now confronted by the massive French force on the plains above Crecy~en~Ponthieu, refused to engage him and fled north toward Calais. The French were confident and very much anticipated a hasty victory. Philip’s force was enormous, composed of the armies of many lords ~ even if made of mostly peasants, they were larger than thirty~five thousand and outnumbered the English three men to one. The French lords and their knights however, were easily distinguished from the host of farmers and tradesmen: the former being well~mounted, carrying banners and sheathed in heavy armor, they had the proud bearing of noblemen and the grim determination characteristic of veteran soldiers.

Long swords, maces and shields clanked against armored mounts; ranks of pikes bobbed amongst the orderly columns of foot soldiers; crossbow wagons lumbered over rutted terrain. A thousand saddles creaked; a thousand horses blew and stamped. Shouting commands were relayed from rank to rank as pockets of men sung songs of the fields and harvests they had left behind. In the wet August air, the sounds of war made a requiem for men who marched stonily toward their fates. Although the soldiers were brash ~ presuming the prospect of a hasty and decisive victory and the taking of many English prisoners ~ within them ran the unease as that of skittish hogs on the eve before slaughter. The shared state of mind betrayed a distinct level of nervousness, spawned more of incorporeal premonition than of any concrete estimation ~ a dim yet thoroughly distracting awareness, running deep through the bone ~ a sense of impending doom. Even the battle horses discerned the very marrow of it; however, the same luminous black raven, perched well above the battlefield in the gnarled oak, apprehended it best of all ~ ‘twas the unseen presence of the Devil herself and, in her company, another ready angel: Death.

In the midst of the column of soldiers, two heavily armored knights with armored horses moved shoulder to shoulder. Over their breastplates hung sleeveless jerkins with identical emblems embroidered. The same insignia decorated their saddle blankets and shields. The knights rode under the banner of Lord Amelet of Laon. They were brothers, separated by six years, bearing the coat~of~arms and distinguished sir name of Blasi. Jean~Jacques and Jean~Rene were the youngest of the three Blasi brothers; the eldest of them was Jean~Francios.

Unlike Jean~Jacques, an unbridled man, Jean~Rene lived with his wife, Alsae Blasi, and his only son, Michael Blasi, in a chateau on the respected Blasi estate, located on the northern outskirts of the town of Reims. Apart from the estate, Jean~Francois resided in a large papal~owned chateau, the Chateau Rouge, in Avignon. He shared the two~story chateau with several other papal dignitaries, their lavish apartments combined under a single roof.

Jacques bit the last meat from an apple and tossed it at his brother’s helmet. The core struck Rene’s raised visor and slammed it shut. Rene snapped it up, exposing a bitter brow, yet holding a forward stare. Jacques laughed and leaned forward on his horse for better inspection of his brother’s stubborn expression.

"Come now, Rene," the young man said with a smile. "Laughter raises the spirit before battle. I’m not King Edward, Le Petit!" Jacques slipped a fresh apple from a pouch draped at his side.

Rene responded coldly, "The men are not prepared for the charge. They are weary from the march."

"I shall run the English into the sea!" Jacques proclaimed, raising his apple on high. "I shall shove an apple in Edward’s mouth and hurl him back across the sea. And since I am your kind brother, Rene, I shall capture an English squire for you," he added with a chuckle before biting a chunk out of the apple.

"They shall position themselves defensively and be prepared for the charge," Rene stated.

"They shall be tired as little girls," his brother countered. "They have seen days of battle. They shall throw down their arms in surrender at the sight of our numbers."

"They shan’t surrender. Both Edward and his Black Prince are with them. They shall defend them to the death. You speak foolishly, brother."

"They are tired," the younger man insisted. "They shall surrender. You are the fool, Rene. I shall remind the fool of whom he is, after the battle; if there be one."

"You have orders, Jacques. You shall follow them, as I. His Majesty’s marshal has ordered every banner rest until the men are fresh from a day’s march."

"Look about you, Rene. Look in their eyes ~ at their spirits! They shan’t rest. Their blood is hot. They shall attack; against orders, even." Jacques replied.

"Many of these men have never tasted battle as we have," Rene reminded him. "And we are bound by orders ~ to Lord Amelet, and whose banner flies for His Majesty," Rene spat. "We have orders to rest. We must not move against Edward until we are given the order to move."

The two men looked over the slow~moving army as a short silence fell between them.

The column seemed to extend itself through the uneven terrain forever before and behind them. Jacques turned to Rene, his face twisted by disgust, and said to his brother, "If these simple men place their lives before the Englishmen, most without shield or armor, then so shall I ride and defend them. True to France, so shall any knight. We serve France ~ these men are France, and I shall defend them!"

"You swore an oath, not to be broken."

Jacques stared forward as though he did not hear Rene.

"Damn you then, Jacques." Rene growled, snapping his face guard down.

Shortly, Jacques asked, "Shall you ride with France, as well?"

Rene raised his visor and replied, "You have lost your balances, Jacques."

Jacques grimaced and repeated the question. "Shall you?"

"You’re no knight ~ an armored fool only."

"Shall you, then?"

"I shan’t confess to Jean~Francois that I was not beside his foolish brother in battle."

"Yes," said Jacques. "‘Tis as he said: The cross rides with both of us, or with neither."

"Indeed it does," Rene sighed. He turned to Jacques and scolded him. "You leave me little choice. You enjoy that, yes?" Rene’s frown fell away, and finally a small smile crept into its place. "I shall ride with the Fool of France." Jacques laughed and leaned toward his brother. "Look about you. I know men’s hearts, Rene, as do you. These men shan’t rest until they throw Le Petit into the sea. The victory is already ours. Soon enough, we shall have Edward’s head ~ and his throne. Show our cardinal brother’s cross, that we may charge to victory."

Tossing the apple aside and slipping off his helmet, Rene pulled a fine golden chain from beneath his breastplate. It supported the considerable weight of a gem~studded crucifix that had belonged to his elder brother, Jean~Francois Blasi, and was since blessed by the late Pope Benedict XII himself. Francois had insisted that Rene and Jacques carry it with them in every battle. As the moment dictated, it was Rene’s turn to wear the Blasi cross. This was a part of the reason Rene felt compelled to join his brother, if Jacques charged: He would not leave his brother to face death alone, and without the cross. Nor would he leave the French army to fight the battle on its own, no matter how foolishly united. To his countrymen and to his brother he was equally dedicated, if in different ways; both he would defend ~ both he would honor. Rene leaned over the side of his horse and handed the cross to Jacques. Jacques kissed the cold metal, bowing his head slightly in reverence. A crash of thunder resonated over the countryside. Jacques laughed and welcomed it as a good omen. Above them, in the boughs of a squat oak, the luminous raven stirred with fluttering feathers. It bolted from its perch into the northwesterly horizon, toward the armies of the English.

"In the name of the most high Lord and Saint Denis," Jacques murmured with stony severity. Rene squared back on his horse and repeated the same reverence. He returned the crucifix to its place upon his breast and pulled his helmet on.

Horsemen raced down the column of armies, shouting, "Make ready! Ready your weapons!" The column lunged forward.

Philip’s army had caught up with Edward, who now had little choice, save to turn and fight. The English king had aligned his mounted knights and pikemen on a wide hill near the village of Crecy, with archers ranked behind and in front of them, and yeomen waiting beside more horses at the rear. Edward held his command from within an occupied windmill atop the hill.

In a short space, whilst continuing in the direction of northeast, the agitated raven covered an expanse of roughly tilled earth and dived into a secluded thicket, hidden by a scant ridge. The bird’s luminous appearance lit heavily amongst the thistle and yew, its harsh call startling a young English archer who stood relieving himself in the lee. "An untoward sign on an untoward day," the archer whispered, staring at the raven ~ and it seemed the bird saw him, saw into and through him, and its unnatural gaze pierced his soul. He buckled to his knees, clutching his head as if attempting to keep it from exploding. He huffed and moaned, crumpling to the ground before dying. The bird shrieked and fluttered wildly before it too fell to its death, dropping into the undergrowth in a feathery convulsion.

The dead archer’s eyes snapped open. He lifted himself from the ground and scanned the hollow. The whites of his eyes were washed away ~ shiny and black as a raven’s feathers. He retrieved a longbow, which stood propped against a tree trunk and, with a full quiver of arrows slung across his back, he left the grove more filled than he had entered it. Even with his bladder emptied, his heart was brimming ~ brimming with the black evil that boiled in his unbeating breast. He broke through the thicket to a rigid formation of nearly a thousand archers flanking five hundred men~at~arms. The formation stood positioned atop a point overlooking a shallow valley to the East. Behind them and to the West, thousands more soldiers waited in two perfect squares. The archer took his place amongst the ranks.

Just as Jacques Blasi had predicted, the French army charged recklessly into the fray before their commanders could restrain them. In the valley, a disorganized mass of shouting men~at arms, spearmen, Genoese crossbowmen, and mounted French knights rushed toward the ridge occupied by the English. There was no order to the melee, the men were knocking one another to the ground in their bloodlust and some even impaling themselves on the swords by their own inept hands.

On the English side of the hill, the soul emptied soldier passed between long rows of archers who held longbows high and drawn.

"Steady! Hold," roared a voice of authority.

The living archers, seeing the blackness of his eyes, poured back, their ranks rippling apart as a parting Red Sea.

Stricken, the men whispered to one another, "Move ‘way! He’s the Devil in him!" None moved to stop him as he turned among ranks and marched down the ridge, leaving the English and their position behind him.

"Archer! Return to your post!" A bellowing order came from behind the ranks. The voice was that of Lord Clifford, certain in its power of command yet the archer maintained his slow, sure course down the hill. Behind the English formation, gray skies broke and the afternoon sun pierced the clouds. With the sun behind the English, the approaching French forces stood blinded.

From his station amongst his own bowmen, the Earl of both Warwick and Oxford called, "Lord Clifford, return your archer! Lords, hold your men on the mark!"

The devil~archer slipped an arrow from his quiver and, without breaking stride, drew it deep into his longbow. His black eyes lay fixed on two bright specs near the far end of the valley.

"Archer! Return or be felled from behind," Lord Clifford demanded. The archer continued down the ridge, his dark figure thrown into eerie relief against the chaos of the advancing Frenchmen. Clifford moved his horse forward, followed by his bannerman.

He stopped beside one of the archers, growling orders to drop the lone warrior where he stood.

"From behind, my lord?" The bowman asked uneasily.

"I order you step forth and drop that man! Do it now, archer," Clifford hissed, gesturing furiously toward the retreating figure.

"Indeed, my lord." The archer bowed and moved to a clear position. He drew back an arrow, tested the wind, and launched the bodkin arrow down the ridge. The shaft flew straight and swift, piercing the soulless man’s back and sprouting from the center of his chest. The impaled archer paused a moment, then turned around to face the ridge. The English soldiers saw only a blur as the dead man turned around to face them ~ perhaps as if to hail them. No one saw the arrow fly from his bow and up the ridge; no one saw that arrow pierce the eye of Lord Clifford’s young bowman. Only when the bowman crumpled to the ground did they see the black~feathered arrow pushing out from his head. The devil~archer turned and continued down the field, into the roaring gape of the French charge.

"Leave him go!" Clifford spat, staring at the walking dead man. "Archers, find your targets! Be ready on my mark!"

Yet, all eyes were on the thing that still walked unaffectedly toward the advancing French enemy and mindless of the lodged arrow, which had pierced through its torso.

The blast of a primitive English cannon echoed across the field as the first hail of arrows rained down amongst the charging Frenchmen. Men and horses fell beneath the onslaught of the arrows, dismaying the French. The arrow shafts had a brand of bodkin arrowheads, new to battle. Bodkin points were long and heavy iron tips capable of slicing through armor. The English longbow were carved from dense Yew wood and fitted with resilient hemp bowstring that required a draw of a hundred pounds or more and hurled this devastating new arrow with incredible force. The metal suit of the French knights did little to protect them.

Seeing his men in disarray and falling quickly, Philip ordered them to turn back and regroup. They ignored the order, charging past him and running through the valley like madmen. The Genoese crossbowmen found themselves in a hail of longbow shafts. Too far from the English, they threw down their bows and fled. Upon seeing this, Philip’s brother, Count D’Alencon, ordered them slain. Thus, it happened that, on that day, more Genoese fell in battle at the hands of their French comrades than by the invading English army.

The soulless archer walked alone on the churning battlefield. Men and horses obeyed the instinctive terror those black eyes inspired, and none would approach the bowman who moved about with apparent unconcern for the arrow that pierced him. He drew another arrow from the quiver on his back, strung and released it in one sure motion. Nearly three hundred yards downfield, the shaft thudded into the earth between the forelimbs of Jean~Jacques Blasi’s horse. Two Genoese crossbow bolts now found their mark in the ribs of the dead archer and a third impaled his thigh. Yet, his black gaze never left its target, and the arrows did not stop him or even slow his hand. Another arrow left his bow before the first was still. This one did not miss. It blazed downward into the collar of Jacques’ armor and pierced his left lung. As he tumbled from his horse another shaft flashed from the sky; beside him, Rene heard a disheartening pop as his own mount crumpled beneath him. A black~fletched arrow protruded from between the animal’s eyes. But the dead archer was not immortal. Even as he released another arrow, a crossbow bolt punctured his throat and he finally fell to the ground. Rene jumped to his feet and ran to his brother. Soldiers screamed past them, their mad charge unabated. Rene lifted Jacques’ face guard, raised his head from the ground, and cradled it in the bend of his arm. His eyes welled with tears; he knew Jacques would not leave this valley alive.

"Do not, Rene," Jacques said, his face struggling between forced smiles and expressed agony. "I have fallen with honor." He coughed on the bubbling blood in his breath. "I wish to ~ to kiss the cross ~ once more."

Rene ripped away his helmet, raised his chin, and jerked on the neck chain until the crucifix tumbled from his breastplate. He fumbled with it, bringing the cross to his dying brother’s lips. Jacques kissed it and he smiled.

"Rene, when you slay Edward, ask the great Jean~Francois de France to pray for me," he whispered. "Swear it."

"I swear, Jacques. And I shall also pray for you, until no breath is left in me," Rene responded with a laugh and a shower of tears. Such was a long~standing jest amongst the brothers ~ the foolish title with which they had teased their ‘overly serious’ older sibling: Francois de France. As Rene pushed the cross back beneath his breastplate, his brother sighed and died in his arms.

Across the valley, the devil~archer stirred. His work was not yet finished. A thick crossbow shaft that lay lodged in his thigh broke off with a gristly crack as he rolled and stood to his knees. A hail of arrows peppered his light armor, however, his blood did not flow; he strung an arrow and released it. Rene raised his face to heaven, wailing in both grief and defiance, even as his own death flew toward him on black wings. Hell’s arrow streaked toward the earth like a soul damned. It scored Rene through the roof of his screaming mouth, impaling his brain and cleaving his skull. He screamed no more. His body fell across his dead brother’s with an expression of horror on his contorting and bloodied face. His gaping eyes did not see the Genoese arrow that took the damned archer through his skull. The archer fell once last, and moved no more.

The English force had consisted of approximately twelve thousand men, over half of them archers. Men~at~arms stood, centering two spreading flanks of bowmen, forming a precise vee of roughly eighteen hundred yards in length. The French force numbered thirty~six thousand. Wave after wave ~ fifteen in all ~ of charging knights raced into the English funnel of arrows, only to heap themselves upon their dead and the ones dying before them. Between the fleeing Genoese crossbowmen, the sun blinding their eyes and the untrained peasants’ mad screams about the battlefield, the French forces began to fall into complete disarray. The battlefield lay riddled with English arrows that stood out amongst the slain men and animals like stiff barley stalks. In the short space of ten hours, nearly half a million English arrows had rained down from the high ridge and over six thousand French and Genoese fell dead. Surely, ‘twas a devil’s dance ~ and a wicked waltz it was.

The witching hour was upon him when the wounded Philip retreated. He had little choice but to abandon his injured where they lay. Two kings, as allies to Philip, had fallen in the horrid slaughter; one of them was the blind King John of Bohemia. Philip had no recourse but withdrawal. Yet, Edward took no prisoners. At midnight, his son, the Black Prince of Wales, moved under cloak of darkness and, with long knives, his men slashed the throats of the injured. In all, sixty~six hundred Frenchman and only a few hundred Englishmen died in the battle. ‘Twas a battle, with which Lucifael was all too involved from the onset. Completely, the credit was hers; both kings, Edward and Philip, were merely pawns in her much grander game. She was the reigning queen, and, unwittingly, two foolish kings jousted as jesters before her.

Following the battle, Philip buckled. With the aid of two Avignon cardinals as conciliators, a truce between France and England was soon in place. Edward retained occupation of Calais and Philip became frantic. The English had removed chivalry from the rules of battle. Hand~to~hand combat, face~to~face confrontation ~ a battle pitting one man’s skill and power and courage against another’s ~ had been replaced by what amounted to spearing an enemy from behind. The English longbow was a slap in the face to the Knights’ class. Although French knights scorned it ~ labeling it as outright cowardice ~ distance combat proved highly effective for smaller armies, like Edward’s. And with Lucifael’s intervention, the art of war had changed and dusk had fallen on the glory days of knighthood.

In desperation, Philip considered seeking out the help of the Holy See and its vast numbers of educated priests. Yet, he required more than prayer of them. He needed finances and a solid counter to the English new weapon ~ the rapid~firing longbow and its armor~piercing bodkin arrow. He needed new strategies to counter the unchivalrous tactics employed by the English. He sought that decisive counter~weapon and the definitive counterstrategy might drive Edward out of Calais and back across the Channel. Nonetheless, Lucifael moved against all thrones, bitterly eager, as a wronged yet outwardly ever mastering Queen~of~queens. The throne of the Holy See and the Papal Palace of Avignon were not immune. The Pope, the College of Cardinals, and Apocrypha Cardinals were all equal prey in her game. And within them all, she wove her web.

Chateau Rouge ~ City of Avignon ~ April, 1347

Avignon’s Chateau Rouge served as guarded residence for several College cardinals. A guard stationed at the rear entrance of the chateau shifted his feet ~ the prickling pain was in his left heel. He searched his boot, yet found no raised tack; no splinter or thorn inside it, however, he felt it again: a prick like a tiny dagger stabbing at his heel. It would allow him no peace. He studied the dead grounds. Not a soul gave sound in the late hour. With a furtive glance toward the arched entrance of his post, the guard stole into the shrubbery that flanked the thick stony walls of the chateau. He patted his pockets hopefully and grinned at finding a folded leaf of paper in a vest pocket. Leaning against the wall, he unlaced his boot and slipped the paper inside it. He was just retying the laces when the long shadow of a hooded figure fell across him. In a panic, he straightened hastily and nearly fell.

"Guard. You are not at your post," the priest said softly. "Why?"

The guard moved toward the archway, looking chagrined, the shadowed figure also moving to block him. "I heard a noise, friar," he stammered. "But ~ ‘twas only cocks, roosting in the bush."

"Ah, roosting cocks. I see." In better light, the soldier saw the priest as tall and rather burly, with full black hair. He seemed to be eyeing the paving stones, however, when his dark eyes flashed over the face of the guard, they were piercing as daggers. "You chase clucking cocks with an unlaced boot?"

"I did not notice it, friar."

"Ah, I see. You did not notice the loose laces." The soft voice was an eerie contradiction to the flashing eyes, setting the guard’s teeth on edge. "Show me your orders, guard. This instant."

Caught off guard ~ he had been wondering when this unnerving priest would leave him to his duty ~ the soldier reluctantly bent and removed his boot. He withdrew his makeshift bandage and offered it to the priest.

"In your unlaced boot? Ah." The priest unfolded the paper and stood beneath a wall torch to read it. "Why are your orders in your boot, guard?"

The guard confessed all. The priest smirked and, returning the folded orders, said, "Then it appears your orders are best when trampled upon. Shall we keep the confession between us?"

"If you would, friar. And how can I be of assistance, Friar ~ uhm ~" the guard struggled for the priest’s name.

"Sevalle ~ Archbishop Lou Sevalle ~ here by personal appointment to see Cardinal Jean~Francois Blasi."

"I shall summon the Master~at~Arms. He can arrange an escort." The guard began to turn away, but the priest seized his shoulder in a painful grip.

"I see by your orders that you are new to this post," the big priest whispered. "I gather you wish no stain against you? I need not wait for an escort; I have been here many times. I shall find my own way."

The soldier, who was indeed a raw recruit and none too quick in the bargain, felt a haze fall over his mind. ‘Twas imperative, that he obeyed his orders; yet, allow a strange man into the chateau, unescorted? An unthinkable dereliction of duty, however, it was equally imperative that he obeyed the soft voice ~ and the command in the flashing eyes.

"Visitors are escorted. I must ~"

"Is it possible," the priest interrupted, "that I did not notice you away from your post? Is it also possible that you did not notice me enter? Do hear me, guard; gather that I am but a quiet roosting cock. ‘Tis late ~ I am weary. Do you gather my meaning?"

Looking away, the guard responded, "I gather it ~ as you say, then. I do not know you. Nor have I seen you."

"A lie in good intent is no ill deed. Well done. I shall see the favor settled thrice as much," the priest said, patting the guard’s shoulder with a sneer the soldier did not see. He disappeared beneath the arched entrance and drifted through the quiet corridors of the chateau. The priest came to a corner, and as he rounded it his features and dress were abruptly changed, metamorphosed into an altogether different form. Instead of a robe, he wore the battle dress of a French knight. On his chest gleamed the gold and gem~studded Blasi cross. He turned another corner and walked placidly through a stone wall, the armor~clad visage melding into the massive stones without a sound.

In the bedroom of Cardinal Jean~Francois Blasi, a hanging wall tapestry fluttered briefly as the form of the knight passed through the solid wall stones. The cardinal tossed and moaned in his gilded bed, his eyeballs rolling under their lids as they tracked the features of a nightmare landscape. Jean~Francois rolled across the huge bed, trapped in dream where he was swiftly falling. Abruptly, he gasped and bolted erect, wide~eyed. Sweat glistened on his brow. The nightmare, when discovered, fled the room. The cardinal’s shoulders slumped in relief and he lay back on the bed, his eyes slowly closing ~ then snapping open again. The nightmare was not over after all. He sat up, his heart fluttering oddly in his chest. There, in the corner of the room, stood the dark silhouette of an armored knight.

"Who goes there?" Francois hissed at it, terror in his throat. The shadow stepped into the moonlight falling through the open window.

"Jacques," Francois choked. "Is it you, Jacques?" His hands flew to his face in astonishment.

"‘Tis I, Jean~Francois. Have you faired well?" It seemed the knight wore an impish grin.

"I ~ indeed, I have! I have prayed for you. How are you? And Rene?"

"Rene preaches, as he always has. He gathered it best that I not visit you ~ he thought it may distress you."

"Oh, no," Francois lied. "Not at all! You must tell him to come. Tell him, Jacques."

"I have come to warn you of a horrible thing, Francois," the knight whispered hurriedly. "France shall fall to Edward of England in the space of but twenty years. Edward shall gain the support of many French lords. He shall come from the west and the north and win the heart of the Burgundy. He shall divide France."

Quite confused, the cardinal replied, "Even with most of the lords of France behind Edward, how might he be victorious? He has no capable army!"

"He shall," the knight said sharply. "He has since sealed a pact with the Devil. ‘Tis the Devil himself who speaks to Edward of the secrets of war! Edward shall take our homeland, Jean~Francois, lest you stop him before his campaign ~ lest you stop him now."

Francois’ mind spun. "That is madness! I can not stop such things. If I speak to His Holiness of this, he shall gather me mad," he said rightfully. "Can you not stop these events, you and Rene?"

"Only you can stop these events, Francois."

"I can not prevent the will of a king, Jacques. Nor can I command of the Devil. I am merely a servant of ~"

"Hear me, Francois." The dark figure was indignant, stepping closer. "The Council of the Apocrypha; you know of it?"

The cardinal stiffened slightly. Reluctantly, he confessed, "I do ~ yet only bits of its truths. What of it?"

"They hide secrets, a weapon of a kind to destroy the English king. You must take charge of this weapon, Francois. You must release it against him. However, first off, you must learn of its proper use. Such knowledge rests in the archives of the Apocrypha, in what some call: the Naramsin Translations. In these pages, you shall learn of the design and workings of this weapon."

"And how am I to lay hands upon these things?" Francois asked, unconvinced. "The archive is well guarded. And they use words of passage to gain access. I do not know these words, Jacques! The archives are for the Council only."

"The Devil shall whisper this secret in Edward’s ear, and Edward shall come for the Naramsin writings. With them, his power shall become greater than even the Holy See. He shall take all of France if you do not heed my words. Francois, you must proceed with this act. If not for France and Church, then for your brothers: that we fell with cause and honor. Even angels fell that the Will of God be done. If others must fall that more may live, ‘tis His Will."

Francois recalled his nightmare. "Others? Who must fall?"

"Even Christ fell, that others may live. I must leave, Francois." The knight turned away.

"A moment more!" Francois cried.

The knight turned back and gave a grin. "You are Francois de France. For the sake of God, do save France. Do save us all." He turned and disappeared through the wall.

"Wait! No! Jacques! Jacques!" Francois bolted from his bed, chasing the fleeting form.

He ran through his apartment chambers and threw open the door, stumbling into the hallway. "Jacques!" Yet, the long corridors lay empty.

His brother’s visage had already crossed the corridor, stepped through the far wall and into a priest’s visiting room. He fell to his knees. "Jacques! Come back!" He sobbed. Doors creaked open as heavy~eyed guests sleepily poked their heads out of doors.

A sleeping priest stirred at the cry outside his chambers, yet his eyes did not open. His bedside oil lamp illuminated the book of scriptures lying face down on his chest, his hands laced across it. The knight stood at the foot of the bed, staring down at the dreaming man. Slowly the plates of the knight’s armor began to meld and change, blending into the gleaming skin of a lush~made woman, her flesh pale as death. Her eyes, nails and waste~length hair were black as pitch; and with wide aureoles ~ red as blood. She was the embodiment of pure and shameless Eve; she was the source from which all women fell ~ and from which all men likewise failed. She was Lucifael. She halted over the priest, smiling. The voices of many women uttered from her pale mouth. "‘Tis a waste of a man to be alone ~ especially, not beneath me. Yet, soon enough."

The priest grimaced, moaning in his dreams, and rolled on his side. The open scriptures tumbled to the floor and her bare heel trampled it as she stepped through the outer wall of the Chateau, leaving only a ghost of profane laughter to trouble the holy man in his dream.

And quite deserving was Lucifael’s laughter ~ less than a month transpired before the wicked seed took root.

Chateau Mallow ~ City of Avignon ~ May, 1347

Unlike Chateau Rouge, which belonged to the College of Cardinals, Avignon’s Chateau Mallow belonged to the Council of the Apocrypha and was the residence of Cardinals Basiliste and Lean. As Lean was in England on a papal mission, the elder cardinal was alone at Chateau Mallow. In his apartment, Basiliste lay fast asleep. Atop his letter desk, a nearly extinguished oil lamp struggled to produce a flame, casting flickering shadows over a nearby quill and inkwell and a composed letter, which bore the words:

My Dearest Cardinal Lean ~

Forgive my lack of fortitude, but the gravest fear has settled upon my soul. I am now convinced that Cardinal Xavier's death was not by chance and dark forces move against us. They seek access to that which we guard. I implore you, return to Avignon at once and together, we shall insist upon an audience with His Holiness, Pope Clement. He must be warned of the dangers. Make haste, my friend. I begin to fear for my own safety.

Yours, in Service of His Holiness ~ Cardinal Basiliste

A brisk breeze killed the flame as the back window eased open to a shifting silhouette. A rouge guard slipped into Basiliste’s bedroom and straddled his chest, slapping a hard hand over the cardinal’s mouth. Then he drew a dagger and whispered the questions he had been told to ask. Basiliste struggled, yet he was too feeble for the strong soldier. In a baleful whisper the intruder warned him not to cry out, the cold steel at his neck making the threat plain. The soldier removed his hand and awaited answers.

In defiance, Basiliste stared at the silhouetted face, saying nothing. The knife moved slowly toward the cardinal’s left eye, leaving a shallow trench of blood. Basiliste gritted his teeth and made no sound. The hand clamped again over his mouth, pressing his head deep into the pillow. With his weight securing Basiliste’s chest, the guard sunk the dagger into the tender flesh beneath the eye. Basiliste screamed through his nose as the knife scraped the walls of his eye socket. The guard flipped the eye onto the floor. When some of the struggle had gone from the old man, the soldier informed him that he still had one eye left with which to bargain.

Basiliste began to speak immediately, telling all he knew. When he finished, the guard demanded that he repeat the code words of passage to ensure they were correct. Sobbing, he swore he had told the truth ~ even so, the knife slipped into the Cardinal’s right eye. Again, Basiliste screamed against the cold hand. Again, he was asked to repeat the words. He gasped and stammered ~ the words were the same. Convinced that he had extracted the information he was hired to collect, the guard shifted himself onto Basiliste’s diaphragm, squeezing the air from his lungs. And after the cardinal fell silent, the assassin slipped over the windowsill and vanished into the still eve.

Some time later, he met his patron in the secret place, arranged after the grisly event. A leather purse changed hands, and the hired killer rode out of Avignon’s west gate and across the Rhone River Bridge. Yet, before he had traveled even a mile, an informed and waiting thief with a broadsword took his head ~ and his purse. The evidence of a vile murder disappeared into the French countryside. And its perpetrator, Cardinal Jean~Francois Blasi, now held the key to the secrets of the Council of the Apocrypha and consequently, the two closely guarded monasteries: Gardiens and Cancello.

Grotesque ~ A Gothic Epic © is legally and formally registered with the United States Copyright Office under title ©#TXu~1~008~517. All rights reserved 2026 by G. E. Graven. Website design and domain name owner: Susan Kelleher. Name not for resale or transfer. Strictly a humanitarian collaborative project. Although no profits are generated, current copyright prohibits duplication and redistribution. Grotesque, A Gothic Epic © is not public domain; however it is freely accessable through GothicNovel.Org (GNOrg). Access is granted only through this website for worldwide audience enjoyment. No rights available for publishing, distribution, AI representation, purchase, or transfer.