Add your promotional text...

Reims, France ~ Chateau de Blasi ~ June, 1348

A late afternoon in June embraced the beginnings of a painted sunset as burning hues of color layered a dying sky. Blasi stood with his face pressed his face firmly against a pane of glass as he peered out of Alsae’s upstairs bedroom window, his breath condensing on it to cause an opaque halo near his full beard. In the stubborn summer heat that lingered in the room, a bead of sweat traced his temple. Even with the disfiguring scars of pitted and discolored flesh that ran the length of his legs, he stood without a cane and in otherwise excellent health. A wooden table stood beside him, supporting a dusty vase of paper flowers that Renee had given Alsae only days before his final engagement at Crecy. The tattered flower petals were evidence to hungry moths that had since dried into a heaping row against the base of the windowsill.

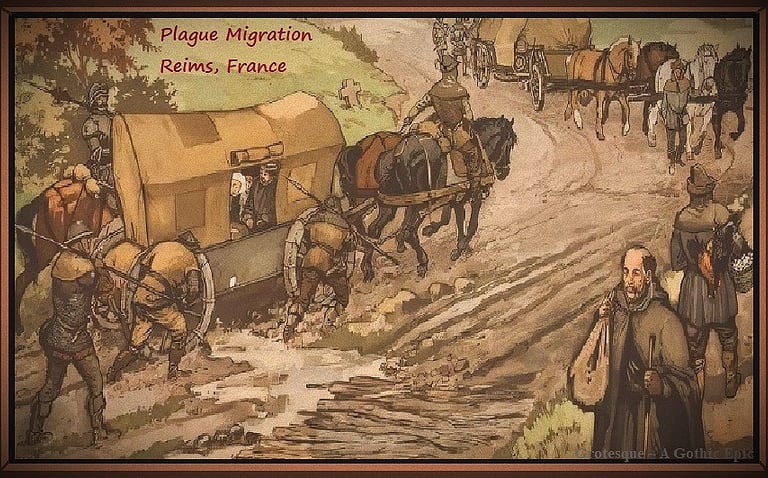

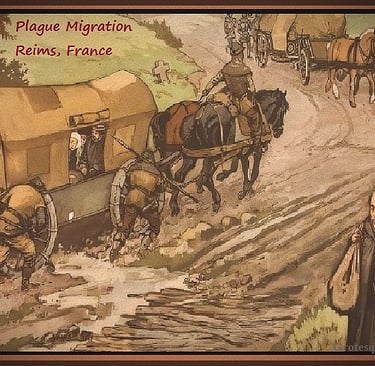

“They are like a line of ants. Who shall bury them all?” Blasi murmured; his glassy eyes fixed into the distance. On the main road that marked the beginnings of the Blasi estate, a steady progression of plague~infected passersby lined the lane. From Blasi’s high and distant vantage point, he saw them as but an unending row of ghostly insects, steadily drifting out of the city before disappearing into the countryside. Young and old, rich and poor, men, women, and children ~ altogether and outwardly moving like the last strides of an entire city, since condemned to the gallows. In the mass exodus, most of them strode on foot, carrying what little they could. Others, who could barely carry themselves, stumbled forth like walking death. Occasionally, overloaded horse~drawn carts sliced through the center of the northerly~drifting column, their wheels barely skirting days~dead corpses that dotted the roadside. Blasi wiped the fog from the windowpane. “Where is there enough blessed ground to inter an entire town ~ or countless cities, even? ‘Tis immeasurable madness; this pestilence is.”

Alsae called to him from over his shoulder and Blasi heard a growing tension in her voice. “If they approach, do not let them in, Francois. We cannot help them. Tell me that you shan’t!”

“I secured the doors and windows,” Blasi answered plainly, keeping his face pressed against the glass. “We are as safe as can be expected.”

A moment passed before Alsae scolded him; “I begged you to leave the chateau! We are in grave peril. For the life of me, I cannot gather why I allowed you to convince me otherwise. A dreadful thing shall happen. Only Ill omen, I feel!”

Blasi refused a reply; instead, he studied the congested road.

“We still have time, Francois! Hear me ~ behind the stables there is an overgrown path through the woods. Renee oftentimes drew his cart through it. We can load the cart and hitch that horse of yours ~

Blasi cut her short. “‘Tis too late, Alsae.”

“‘Tis not! And if Michael should die at the hand of your doggedness ~ can you bear such a cross? Can you, Jean~Francois Blasi?”

“He is safe,” Blasi stated. “And you are safe. In our faith, we shall be fine.”

Alsae sighed and grumbled, “Only if the Lord allows it; and I pray hope that He shall.”

Blasi nodded. “He shall.”

“What is more, Francois; I do not want you secretly telling Michael that he is going to ride that unruly steed. You ought to have kept the other, as I insisted.”

Blasi crumpled his brow and dropped his shoulders. “Must we mull over that, again?”

“We must!” she exclaimed. “We must, if you are to keep so many secrets. Do you not recall me to be the eager wife of your brother and the loving mother of your nephew? Have I not always opened our humble home to you? Have I not always cared for you in time of need? I am not the English, Francois, and I did not slay your brothers!”

Blasi spun about; his eyes red and swollen. “Why must you pain me so? What do you wish from me, otherwise?”

“I want the truth!” Alsae exclaimed. “I beg of you.”

“Ah.” Blasi dropped his head and chuckled. “Only, the truth?”

“Yes; I wish to hear Jean~Francois tell me all of the truth that Cardinal Blasi has kept from me. Can he fill this one humble request for me?”

Blasi searched the room as he considered her straightforward but outwardly impossible request, yet no single bedroom fixture could command enough of his gaze to dismiss her eager stare. He bit his lip, dropped his shoulders, and sighed heavily. “If you insist, then I shall tell all.” He turned his back to her and stared out of the window before continuing; “And when you come to learn the truth, then I hope that you might find a place in your heart to forgive me and perhaps appreciate my initial reason for not being utterly forthright.”

Alsae admonished him. “The truth, Francois.”

Blasi complied. “Very well, then. It began in my chambers, in my apartment at the Chateau Rouge, in Avignon, when I awoke to a most unexpected visit.” He leaned himself against the windowsill, watching the steady progression of the passersby as he confessed all ~ of his fortunate opportunity to behold Jacque’s spirit ~ of the difficult entry into the Apocrypha Archives ~ of the discovery of gatestones hidden by the Holy See ~ of King Philip, Pope Clement, and a papal plan that included a loan ~ of Captain Bourne, Abbot Vonig, and his arduous stay at Abbaye des Gardiens ~ of the eventual opening of the gatestone ~ and, of his terrible injuries and his narrow escape from the abbey on the captain’s horse. And throughout the entirety of Blasi’s expressed recollection, Alsae did not interrupt him. In conclusion, Blasi turned about, stating, “There, you have it. All of it, Alsae.”

Alsae pointed a trembling finger toward the table beside him. “The old papers over there; those are the pages of which you speak?”

Blasi shifted himself away from the table and nodded guiltily, admitting, “Most of them; others were lost to the wind.” He turned away, giving his attention back to the congested road. He sighed. “There is no more to tell, Alsae. Please forgive me for not revealing it before now.” Blasi set his jaw and stiffened in anticipation of a harsh rebuke, yet only a tomblike stillness settled betwixt them.

At length, Alsae dispelled the lingering silence with renewed vigor. “I cannot hear Michael! Perhaps he is outside ~ with them. Francois!”

“Not to fret; he is resting,” Blasi reassured her, “Safe as he can be.” Continuing to peer through the window, he turned his gaze slightly and looked at an ancient poplar tree, with its largely spreading limbs.

“Splendid,” she responded, her voice more relaxed and perhaps laced with even a hint of humor. “Francois, he’s been a little sprite all day ~ wore me to the bones. So much spirit in him ~ just like his father. He shall one day win the heart of some lucky lady like me. And woe to the woman who is swooned by his charm.”

Blasi choked; a new tear chased another down his cheek and disappeared into his beard. “We are safe,” he replied, staring beneath the poplar tree at a small wooden marker with a mound of dirt before it. He had only buried the boy on the day before.

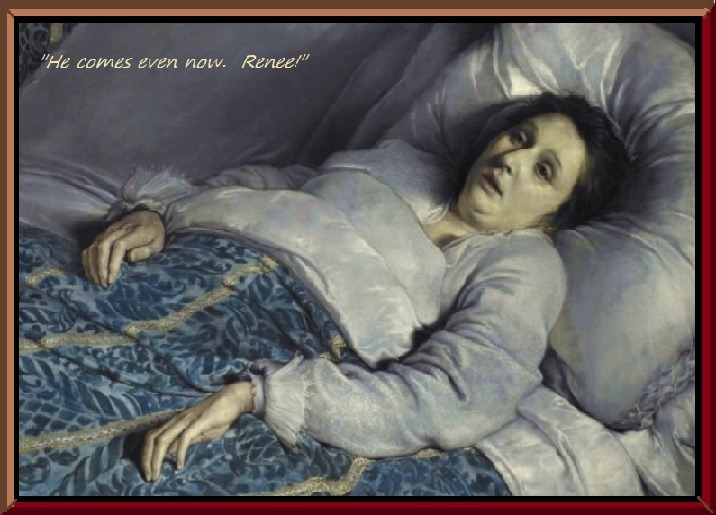

Alsae offered her own confession; “I have something to share with you and I shall be forthright, as well. Whilst you slept, I went to the bakery for fresh bread. You had best be hungry; your dish overflows. And you may be delighted to know that your brother shall be joining us for dinner.” She chuckled. “And this time, he gave his word that he arrives before sunset. Oh, listen! He comes even now. Renee!” Alsae sighed deeply.

“You must rest. I shall bring food, water, and fresh linens,” Blasi responded as he rolled himself away from the window, his eyes coming to rest upon Alsae as she lay slumped over the side of her bed and drenched in sweat. Her delicate upturned arm extended past her mattress, suspended in the air, as if reaching out for something or someone unseen. Her fingertips were black; her smiling lips, dark and parched, and her glassy stare lay fixed on nothing more than maybe a crease in the ceiling.

The following day, Blasi labored beneath the old poplar tree, between fresh mounds of earth, scattering shovelfuls of dirt over Alsae's grave and covering his last relative of the once~prominent Blasi lineage. He speared the spade into the ground and raked his foot over broken roots when he discovered an overloaded cart parked at the front entrance of the chateau. Blasi shielded his eyes from a sunny glare to better inspect the uninvited person. Against a backdrop of sickly passersby, the driver remained parked, watching him as perhaps an unabashed voyeur. A strip of cloth wound completely around his head, save for a naked area that offered merely a darkened slit where a pair of eyes would otherwise exist. He could have resembled a mummy with a wide~brimmed hat. The driver sat in the noonday sun with a long coat draped over him. In his ominous appearance and faceless countenance, had he not openly revealed himself in the light of day, Blasi might have gathered him to be Death, Himself, parked on a corpse cart. Yet, when the outwardly peculiar spectator showed no sign of further advance, Blasi dismissed him and gave attention to more grave and immediate concerns.

The cardinal retrieved a flask of aged vinegar from the base of the tree and sprinkled its freshly consecrated contents over Alsae’s grave, reciting that which Michael had naively deemed to be: the other words. At length, his words complete, Blasi genuflected near the foot of her plot and closed his prayer with a departing salutation; “Go with God in Christ, Alsae Blasi; loving wife of Renee Blasi; caring mother of Michael Blasi. Amen.” He marked himself in the sign of the cross and bowed in quiet respect ~ and retroflection. And in the hanging moment; in the absence of bird song; in the monotonous hiss of summer crickets; in the itching and dizzying heat of the day, in the dawning of his forlorn condition; and in the disquieting revelation that his any expressed plea for forgiveness would forever fall on deaf and dead ears, Blasi wept. He slumped to his knees and fell atop the mound, raking fistfuls of dirt into squeezed clumps as if, by some divine means, a more firm grasp of the moment might help to pressure Alsae from out of her terminal condition. There, beneath the poplar tree, between soiled hands and heaving sobs, a flood of cries watered the dirt. And there, beneath the poplar tree, Blasi doted upon the delicacies of his disappointments as he entertained an overwhelming emptiness, drowning himself in a zealous mix of hindsight and sorrow.

‘Bon après~midi, monsieur!’ The unexpected call jolted Blasi, quickly reeling him back to reason. He leapt to his feet and spun about like an unsuspecting criminal, wiping his eyes to discover the forthcoming driver and his rocking cart. The stranger removed his hat, unwound the cloth about his head, and peeled away the long coat. He revealed himself as a middle~aged man with a hollow face and a heavy beard. Conspicuous dark circles beneath his eyes suggested him to be a weary traveler. In slow approach, the driver waved a welcoming hand. “Comment allez~vous?”

Blasi commanded of him with a staying hand, “Arrest your steed!” He rushed from beneath the tree and sidestepped into the clearing. “Come no further!” The driver quickly halted and his horse protested with several nods against the tight reins. Blasi pointed to the chateau as he shouted to him, “The master of this manor commands an army! Take your leave, forthwith, or be slain by his hand!”

“Je m’ appelle, Jean Labatut,” the cart owner called out, introducing himself; “I am a prominent merchant from Marseilles. Forgive me for troubling the master of the manor; however, I would deeply appreciate an audience with him, if I may be so honored.” He wiped his brow against his sleeve. “You have my word that I bring no ill will ~ only my prayers and a promise of good intention, of which he might greatly appreciate in these troubling days.”

Blasi neared the cart, scrutinizing him. “Make known your good intention.”

The man fell into a coughing spell, only nodding and pointing at the base of the poplar tree before managing a raspy reply; “You prepare fresh graves.” He swallowed hard and cleared his throat. “‘Tis consecrated ground, yes?”

“‘C'est ainsi,” Blasi affirmed.

“Blessed properly ~ by a priest?”

“C'était ainsi,‘” he again confirmed.

The man sniffled and carefully studied the grounds as if searching for something particular to him. “And how much a part of these grounds are consecrated?” His eyes came back to rest at the tree and he looked it over, from its highest boughs to its roots.

“Enough; what do you seek?”

“If the master allows it, I wish to barter with him, a simple service for all of my wares.”

Blasi stole a glimpse of the chateau entrance. “He speaks to no one, save me. Tell me of your proposition and I shall promptly convey it.”

“Yes. I wish to ~ if the master is willing ~” The man grimaced and scratched his scruffy beard, considering how best to present his good intention. “Please inform him that a merchant has arrived with a trader’s cart filled enough with wares to supply his entire manor for several seasons.” He peered over his shoulder and scanned his goods before reciting his inventory as any effectual merchant, honed finely by many years of crafty dealings; “I have fresh grains, dried fruits, salt~meats and sweetmeats. I have lamp oil, scented powders, balms, cloth, leather, and medicines. I have a plentiful supply of salt and all manners of curing and healing spices. I have cooking irons, porcelain pieces, and serving dishes of silver and gold, fit for any noble abode. As well, I have an untapped cask of the finest wine in all of France.” He turned about, looked squarely into Blasi’s eyes, nodded, and passed a presenting hand over his horse and wagon, solemnly saying, “And this fine mount and sturdy cart are also a part of my barter, if the master is willing. Please inform him ~ all of this, I shall give him, if he grants me but a simple request.”

Even in his less~than~presentable condition, the merchant exhibited such a pristine presentation as to capture the concentration of an equally crafty cardinal. Blasi examined the equine’s legs, teeth, and eyes to find the beast to be a fine young muscular steed with an unblemished coat that seemed to cast a crimson sheen against a glare of sunshine. He narrowed his eyes, suspicion brewing within. “And what, might be this simple request?”

The man shifted himself in his cart. He cleared his throat and poignantly admitted, “The pestilence has me. However, in exchange for all that I own, I only ask that I may be granted a bit of hallowed ground for a proper burial.”

Blasi retreated several paces and clasped his fingers before him, considering the unusual request. He cast glances between the poplar graves and the sickly merchant before attempting to dismiss the plagued stranger’s proposition. “I no longer believe ~

The man interjected, “I beg of you!” He pointed toward the rear of the grounds. “I can remain outside the chateau, in the cart; back there and near the wood~line. I require no care at all.” He dabbed a cloth against his neck and continued his plea; “My time is short; perhaps a day more and I shall be no further burden. I ask not even for a stone by which to mark me; only a plot on holy ground.”

Blasi thoroughly inspected the merchant’s cart, which carried an impressive cargo and appeared heavily modified from an original design. Numerous vertical planks stood tall, strapped to its every side, all of them containing metal fasteners from which a web of ropes crisscrossed between, and through the high stack of tightly packed provisions stowed within the cart. Wondering how the wheels of the cart were capable of supporting such weight, he noticed the uncommon width of them. Blasi’s eyes came to rest on the topmost edge of a miniature wine cask that seemed to peep out at him from behind a bundle of burlap sacks. He drew a deep breath and looked over his shoulder, passed the rear of the chateau, over a thick field of weeds, and to a more distant row of woods that marked the darker borderline of the estate grounds. He turned back to the man and searched his face in a good light, sensing the tradesman’s offer as genuine. After all, Death did seem to have staked its claim, itself completely waxed and ripe in the man’s angst~ridden gaze. Blasi knew the signs and the mark ~ an unmistakable aura of fate, mortality, and holistic obscurity outwardly cursed the man’s presence like a lingering black radiance.

The cardinal motioned him forward as he returned to the old tree. “Move your cart to the line of woods.” He retrieved his shovel and strode toward the back entrance of the chateau as he called out; “Remain there until I return with reply.” The driver complied, parting a sea of weeds as he carefully steered his cart through a field of tall brown canes that crunched beneath his wheels.

Blasi entered the chateau and stepped inside the hearth and kitchen area, propping the shovel in the corner before closing the door. He stood and rubbed the gritty sweat from the back of his neck, ignoring the enduring stench of vomit and bile that engulfed him as he contemplated what to do with his new deathbed~guest ~ one who owned enough cargo to provide him with ample reserves for the coming winter months. Blasi knew that, with the pestilence now devouring the nearby city of Reims, the man carried on his cart, perhaps more provisions than those that existed in all of the town’s shops. Yet, even with keen attention paid to reason; and with all that the merchant had promised him, the wine cask stood foremost in his mind as a tempting elixir, which Blasi felt to be a staple ingredient of his interim existence, if he was to drown the plaguing memories of Michael and Alsae. More than food or life itself, the wine was enough to still his guilt ~ to quell his conscience, if even for a short season.

He moaned, kicking through scattered refuse as he approached a streaked window. He waved his hand through a swarm of blue and green flies, peered through the grime~stained glass, and looked over the stalk~covered field to see the topmost of the merchant’s cargo, now stationed near the rear wood line. A figure moved and Blasi discovered the man now standing high in his cart and looking about, apparently inspecting the overgrown grounds. Blasi smirked before addressing the merchant with a whisper and a highbrow demeanor; “Oh, dying man; can you not sense its omnipotence in every breath you take? ‘Tis everywhere ~ an infestation of growing decay in every move we make. Death is immortal ~ the crux of life that shall outlive us all.” He chuckled like a drunkard and stumbled away from the window.

Blasi stared at the cluttered floor as his smile disappeared beneath the gradual hardening of his face. His brow fell with a tightening of his jaw, his one good eye burning a hole through the flagstones. Only then did he become aware of the rancid odor that permeated the space about him. And only then did he acknowledge the picturesque display and still life presentation that centered the room ~ that of a large rough~hewn table and its graphic contents. The table appeared as a well~used sacrificial altar, with heaps of soiled linens spilling over its top and sides. Bloodstains and other bodily excretions hardened the cloth into stiff layers of irregular form. In the midst of them, a crusted wooden washbowl lay as evidence of his fervent efforts to bathe and wash the fevers away. Flies played on its rim and Blasi pursed his lips, staring at the crude spectacle.

“No!” he exclaimed, plowing through the rubbish. “You shall never ~

Blasi grasped the side of the table and heaved, toppling it sideways as the bowl clattered against the floor. Clouds of flies arose and the room settled into a steady hum. “Ne~ver!” He leapt backward, frantically searching the walls and ceiling of the room as if to look for something in particular. Blasi threw his arms wide and spun himself in circles, laughing and screaming at the entire enclosure, “Look at me! I am still here! You have done nothing! You cannot touch me! You fear me! You shall never ~

Blasi slapped at the flies, flailing his hands about his head, and lost his footing in the rubbish. He struck his crown on the floor with enough force to send his mind reeling. And he lay still as a dead man, the memory of Michael’s voice haunting his being: ‘I’m going to be an angel and have wings~ and fly~ really, really fast~ so the Devil can't catch me!’ Blasi moaned and opened his eyes to find his hand beside his face, a fly perched atop a scraped knuckle. For a moment, he lay on the flagstones and watched the insect rub its legs together, its over~sized crimson eyes staring back at him. Then it took flight and circled lazily in front of his face as the voice of Michael continued in his mind: ‘Like this, Uncle Francois! Like the wind? See how fast I am?’ The fly lit on Blasi’s face, inspecting the trail of a new tear that dripped from off the tip of his nose. More tears coursed the same; Blasi sobbed and the bug flew away.

Beneath a drone of flies, lying in the waste of the once~coveted and distinct Blasi estate, the cardinal withdrew into the furthest recesses of his mind, and to a region thoroughly disconnected from time and space ~ to a place where gloom, loathing, and confusion might mingle with distorted memories and troubling dreams to manifest an outwardly monstrous and unnaturally~fused state of sick complacency, grotesque cynicism, and unnatural concoctions of absurdly incongruous recollections and reflections, altogether spawned and forged from some placid black pool of abject madness. There was no sharp sound akin to cracking wood or shattered glass~ not even a hint of a thud, thump, rip, or tink that might convey a breaking thing. There was absolutely nothing, save an unbroken silence; yet in the stillness of that deathly quiet and pure state of transcendence, Blasi's mind slipped, if only by petite degrees.

The cardinal’s demeanor changed completely as he chuckled and sat upright on the floor. He pressed his wild hair back into place and searched the walls of the room, his eyes glazed and rolling like those of a drunkard. He nodded, smiling. “I see.” He stood up and slapped the dirt from his pant legs. “Indeed, I do,” he replied, throwing his hands on his hips, continuing to address the walls, “You took them from me because you wanted to torture me with a most personal loss ~ and shield me from the effects of this worldly pestilence, when all others succumb to it, because you wish to keep me alive so that I might give you a long life of grief, upon which you would forever feed. However, if I die, then you no longer have satisfaction of my grief. No, No! NO, I refuse to grieve for the likes of you! Alive or dead ~ either way, I have undone you.” Blasi laughed and dismissed the wall with a petulant wave of his hand. “Now, be gone from me, Oh Death and Grim Despair! I have a real guest in the wings, if only for a spell.” He adjusted his clothes, checked himself like any prim and proper dignitary expecting an audience, and stepped out of the chateau with a subtle grin, high brow, and a raised chin.

Blasi strode through the high weeds and stopped amidst them, calling out to the merchant and gesturing for him to approach. “Bring yourself and your cart to the rear entrance of the chateau! The master accepts your offer ~ the wine and the provisions in exchange for room, board, and a proper burial!”

The merchant shook his head. “‘Tis best that I remain here, lest the master invite the pestilence upon his house!” Blasi watched him climb down from the cart and disappear in the cane field, only his voice marking the direction of his whereabouts as he continued, “If the master wishes, I can remain beneath these trees whilst his soldiers unload the cart!”

“He does not wish it,” Blasi exclaimed, waving him forward with a welcoming hand. “Neither haint, nor hand of death is of concern to the master of the house. Accueillir, Monsieur Labatut!”

Save for hissing crickets, a brief quiet fell over the field before the merchant questioned Blasi, “Is he also dying?”

“He is not. Now bring yourself and your cart, and, only then shall he honor your request.” Over the weeds, Blasi saw the man climb into his cart and steer it towards him. “Does the master have a priest in his house?”

“He does, for a spell, and he shall tend to your needs.” Blasi motioned him toward the chateau as he returned to the back entrance.”

“Are you that priest?”

Blasi called from over his shoulder, not missing a stride. “As you might have gathered, I am. Consecration, absolution, and last rites seem to be a preoccupation of mine these days. Come! I have an empty room and a thirst for wine.”

The merchant parked his cart beside the entryway and the two men began unloading, stacking its contents in the kitchen area of the manor. When they had moved nearly all of the provisions into the house, the merchant slipped a sack of grain from off his shoulder, placing it inside and atop a similar sack that Blasi had also stacked. The merchant huffed and complained with a heavy breath as he leaned himself against the toppled table; “I did not gather that my unloading my own cart was part of the exchange.” He surveyed the interior entryways that led deeper into the house and upstairs. He sighed, wiped sweat from his brow, and questioned Blasi, “Where are the master’s men? This is absurd; are they sleeping? I am dying as I move these provisions to keep them alive.” He shook his head and winced. “And what goes here? The stench ~ the waste ~ how does the master permit ~

The merchant scanned the fly~covered, soiled linens and turned toward Blasi, studying him. “Death was here. You are the only survivor in the chateau, yes?”

Blasi approached him, leaned against the table, and shook his head. He looked squarely at the merchant and smiled. “Death has left this place. And in truth, there are no soldiers; however the master is here.”

“I hear no cough or sneeze ~ no sign of life, save these pestering flies,” he refuted, pursing his lips and waving a dismissing hand in front of him. “You are that master?”

Blasi chuckled. “As myself, I can only wonder of being so prominent and illusive.” He looked about the room with a staged expression of grave suspicion as he whispered to the merchant, “The master listens to us even now.”

The man narrowed his eyes before searching the room and speaking loudly enough for his voice to carry, “In my years, I have walked openly in the company of kings and their vassals.” He propped his hands on his hips and addressed the walls; “I am Jean~Baptiste Labatut, Master Broker of eastern imports.” When he heard no reply to his self~introduction, he questioned Blasi with but a whisper, “If the master is as prominent as you say, then he might have a name by which I know?” He leaned closer. “His title?”

Blasi patted the man’s shoulder. “Oh, everyone knows him. And shortly, you shall have your audience with him. As with all of his company, I suspect that he awaits yours with genuine anticipation. Now, for the wine; shall we?” He spurred the man into motion and they stepped out of the chateau.

The cardinal rounded the cart and inspected a faint insignia on the wine keg when the merchant approached him. “Why must even his title be so secret that you cannot even whisper it to me?

Blasi shrugged. ‘Tis no secret. The master answers to many names, yet his true name is Death.” He turned his attention back to the keg, adding, “A rather common yet noble name in the same ~ what think you?”

The merchant went pale and he stepped back. “I think that the priest chooses his words in very poor taste, considering my condition.”

“I mean you no ill will,” Blasi replied before pointing toward the two graves beneath tree. “Just as I do not mean them any disrespect. I see only that which I cannot help but witness. Truly, I would like to see nothing beneath that tree; however, I see graves. I would like nothing more than to have known that my brothers fell bravely at Bethany, instead of Crecy, and then discover that they arose from the dead; however, I see their faces only in my dreams. I would like to see nothing traveling the roads of Reims; however, they city is busy with dying ~ you, included, and I must now bury another. And I would like to rest my weary legs and sip some wine; however, here we are, in the scorching heat of day, with the wine keg still in the cart and entertaining the master that I so desperately despise: Death.” Blasi huffed and climbed into the cart.

Labatut followed him, asking, “Your brothers are beneath the tree?”

“No. Death is beneath the tree ~ ‘tis everywhere. The master has claimed even me ~ I am also dead.” Blasi groaned, tilting the cask gently on its side as he instructed the merchant about carefully moving the keg; “Now, we should gentle with her, lest she get away from us.” Suddenly, the horse jolted, shifting the cart and causing the merchant to fall against the keg. The container rolled toward the rear of the wagon as Blasi scrambled over him, stopping it from crashing to the ground. He held the cask in place until the wine settled within. “Gently, I said! You step like a cow!” He glared into the pitiful face of the merchant before resting his head atop the keg. Then he drew a deep breath. “Perhaps I lost my head for the moment. Forgive me, Jean~Baptiste. ‘Tis only my concern; that this is wine is special, as you mentioned.”

The merchant wiped the sweat from his eyes and crawled toward the rear of the cart, saying, “‘Tis the finest wine in all of France.” He stopped beside Blasi, put on a smile, and whispered, “And I witness a thing as well ~ that a dead priest suffers a terrible thirst for his special wine. Might we oblige him?”

Blasi nodded.

The two men worked with the keg, positioning a pair of landing planks against the cart to offload it.

Labatut adjusted the pitch of one of the boards and stifled a cough. “You know that the pestilence has me, yet you do not keep your distance from me. It appears that the Lord has blessed you, yes?”

Blasi stood still. He scratched his beard and contemplated, briefly inspecting his finger before nodding. “It appears so. And as I have witnessed only a moment ago, a tiny angel descended upon my hand and told all.” He propped himself against the rear of the cart, picking at a scrape on his knuckle. “Then it became clear to me that difficult questions do not have difficult answers, but simple ones. The only seem to be difficult because they are not a part of what we expect in an answer. Thus, our expectations oftentimes dictate what we will accept as credible answers to our questions. Do you gather me?”

“Uh, no, I do not,” the merchant admitted. “I merely asked a simple question. Why are you not dying, like everyone around you?”

Blasi stepped away from the cart and laughed, holding his hands out in presentation. “You see? Even you cannot see the answer to your question because you cannot see passed what you expect to see.”

Labatut frowned. “I see that, either you practice speaking in circles or, you do not wish to answer me, or that something is the matter with you.”

“Ah!” Blasi cried, pointing his finger in the air. “You answered your own question even though you refuse to accept it as an answer.”

The merchant huffed and leaned against the cart. “Which part is the truth, then? That you refuse to answer me?”

“No, the latter part is the truth ~ that something is the matter with me.” Blasi pursed his lips and winced before continuing. “When you asked me why I am not dying like everyone else, you expected that I could die. Can you see that you cannot see past my being alive? As I told you, I am not dying because I am already dead.” He laughed. “The dead cannot die ~ there is no second death.”

Labatut stood up from the cart. “You do not jest. You really do believe what you say, yes?”

“You see? The answer was not difficult, after all ~ only different from what you expected.” Blasi nodded, winking.

The merchant dismissed Blasi and wiped the sweat from his brow, voicing concern; “The day is short. I grow weaker and you plainly need a drink. We’ve a cask of wine to move and a proper burial to arrange. Shall we?”

Meticulously, the two men managed to move the cask into the kitchen, setting it upright in the most interior corner of the room. The merchant leaned over it, panting heavily. Blasi slumped against the wall and caught his breath. “Where are the palace squires when you need them?”

The merchant looked up at him. “Which squires?”

Blasi shook his head and rubbed his shoulder. “Squires or no, we moved it ~ we need it.”

“We? You need it.”

Blasi stepped away from the wall, stooped, raised his pant leg, and proceeded to remove a splinter from the wine keg, which he felt to be, beside his knee. He picked at the wound as he spoke. “No, my friend; the most painful part of death is its final hour, and you shall beg for this wine, when such time arrives.”

The merchant crumpled his face and straightened himself as he examined the exposed leg, with its thick, pitted, and deeply discolored skin.

Blasi plucked the splinter from his knee, licked his thumb, and wiped a trickle of blood. He stood found the merchant’s expression of disgust. “‘Twas but a splinter ~ I shall live.” Blasi smiled.

“Indeed, you shall,” the merchant replied, “More so than most.”

Blasi’s smile faded. “What do you mean to say?”

“I mean to say that you seem to be either blessed or cursed to outlive the rest of us.” The merchant pointed to his leg. “You show me burns that would have killed any other man. And here you are, with me ~ with the pestilence beside you ~ and you are more troubled by a splinter than catching your death.” The merchant nodded, suspicion gathering on his face. “There is more to you than mortality, it seems. Who are you?”

Blasi smirked and raised his eyebrows, pretending to be mysterious. “Perhaps I am blessed by an angel?” He reassured the merchant with a pat on the shoulder before escorting him up the stairs. “Only the Lord knows what is best for us all. Now, I shall settle you in. You shall be comfortable. Unlike the condition of that which is downstairs, the upstairs bedroom is tidy and clean.” He chuckled. “As a whole, this place might resemble heaven and hell, all rolled into one house.” The merchant attempted to stop on the stairs and look at him, yet Blasi pushed in upward. “Not to fret. As agreed, I shall care for you ~ and see to it that your burial is as proper as that, of any deserving man of God. For now, you must rest. And we shall indulge ourselves with good wine and company, this eve.”

Time passed as Blasi settled in his dying guest, extending him the hospitality of Alsae's upstairs bedroom. Thus, the merchant slept while he parked the cart by the stables and tended to his newly acquired horse. He fed and watered the animal, eventually securing it in the last stall that once held the untamed black horse, which escaped. Several hours lapsed and, under lantern light and stars, he returned to the chateau. He lit oil lamps, tapped the keg, and woke his rested guest with two goblets and enough wine in a wooden washbowl to send even a pair of horses into a drunken stupor.

Blasi slid the washbowl and wine goblets atop a bedside table. “You’ve slept for much of the afternoon. How do you feel?”

The man eased himself to a seated position on the side of the bed. “As if trampled by the Devil himself,” he groaned. Beads of sweat rolled down his face. “I dreamt that we were digging my grave. Yet, we lost the dirt. I was looking for my dirt. Dear God.” Blasi watched him scan the room as if still searching for it. Then he spotted the washbowl and goblets. “You tapped the wine?”

“Yes. Shall we?” Blasi played host, retrieving both empty goblets and extending one to his guest.

“Perhaps in a moment,” the man rubbed his throat and swallowed hard, his face crumpling as if in pain. Blasi returned both goblets beside the washbowl and approached the window. He crossed his hands behind him and stared out at the front road. Several distant torches moved in line, slowly adrift in the darkness as perhaps a column of lazy fire~specters attesting to the continuing mass exodus from Reims.

“You said that your name was Labatut?” Blasi questioned.

The man coughed and cleared his throat. “Jean Labatut.”

“I seem to recall it.” Blasi turned around and stared at the merchant’s boots. “You said that you come from Marseilles?”

“Marseilles, yes.”

“Tell me, how did you come to acquire this wine?” Blasi inquired with a nod toward the washbowl.

“Well, I come from Avignon, but originally from Marseilles. I left Marseilles when the pestilence first arrived.”

“Aha!” Blasi snapped his fingers. “You are the Jean~Baptiste Labatut; the Avignon merchant who’s shop sat opposite a blacksmith’s ~ down the lane which led to the Curia cemetery, yes?”

“I ~ Yes. How did ~”

Grinning, Blasi stepped nearer to the bed, rubbing his beard, maybe as if unraveling a mystery. “And your faithful fleet of cart couriers made routine trips to the port of Marseilles, where they secretly traded casks of wine with the Genoese merchant ships in exchange for imports coming from Kaffa and bound for Genoa.”

“Have we met, before?” the merchant asked.

“But not just any wine, mind you.” Blasi ignored his question and shook a pointing finger, “Heavenly ferment from the finest fruit ~ these casks came from the Great Cellar of His Holiness’ humble abode: the Pope’s Palace.” Blasi chuckled.

“How do you know this?” The merchant shifted himself on the bed, outwardly expressing a growing unease.

But the cardinal continued, driving his speech home. “I wonder how it happened that the Genoese never noticed the many discrepancies when they compared the ships’ records to what they unloaded. And I also wonder how the palace inventory scribes failed to notice so many missing wine casks.” Blasi sported a satisfied grin. “Unless, of course, neither part of the ships’ merchandise nor part of the papal casks found themselves recorded as inventory, initially.”

“You are no priest. Who are you?” The merchant glared at him.

“I am actually a cardinal.”

“And I’m a flying steed,” the man spat.

Blasi laughed. “I recognized a mark on the cask before we moved it ~ the same mark that I always carved into the sides of wine casks and set aside for your couriers to pick up. I only marked the best kegs of the season.” He nodded. “It appears that we were partners proven, for a time. And a profitable exchange it was for the both of us, no? Perhaps ‘tis a blessing that we finally meet, face to face, after these many years, however, regretful under such grave conditions.”

“Your Eminence? Cardinal Jean~Francois Blasi?” The man asked, incredulously.

Blasi raised his hands, palms out. “I am he ~ your faithful and former wine provider, again at your service.”

The merchant chuckled. “Well then it seems that you know of a part of my confession even before I tell it.” He shook his head. “And I often wondered what this cardinal did with the imports that I traded him.”

Blasi slipped a long~stemmed paper flower from out of a nearby vase, answering him with a high brow, “As you might know, the College of Cardinals is a body of unlike minds. One must secure the loyal support of others, from time to time ~ gifts and such. Being a merchant, I gather you may understand what I imply,” Blasi twirled the flower, smirked, and winked at him.

The merchant chuckled. “You are no better than I, for your part in it.”

“And I never claimed as much. However, those days are dead and our deeds long buried without record. And even today, neither the glorious Holy See, nor the magisterial Genoese nobility notices anything unaccounted for ~ both are wont to an overabundance of everything.” The cardinal smiled weakly, inspecting the flower’s paper petals with his fingers. “Such is the apathetic blindness of the seats of all great authorities, no?”

Blasi smelled the tattered bloom and blew dust from its petals. “Yet it appears that a similar misfortune bit the both of us. You are no longer the wealthy merchant that I recall and I am no longer the clever cardinal that you last remembered.” He tossed the flower on the floor and crossed his hands behind him. He rocked on his heels. “Oh, but you might find something of an amusement in that one of your smuggled Genoese imports now sits in His Majesty’s Palace ~ a rather curious tripod device for cooking an egg. It contained two oil lamps, with blue dragons painted on it.”

“I recall such a device ~ an Egg Window ~ three of them on my last run to Marseilles. My courier gathered them to be of exceptional value ~ the only reason he accepted them in trade. The merchant piled pillows against the headboard and propped himself upright. “So, a gift to the king, was it?”

Blasi approached the side~table.

“Not exactly ~ more, a part of an exchange.”

“For what?”

Blasi laughed. “Well, if you must know: To secure an army.”

“An army?” The man cut him a critical eye. “And I’m a blazing red steed. But, do tell all.”

“If I told you the whole of it, then you would certainly not believe me.” Blasi dipped both goblets into the washbowl. “Perhaps we might now partake of the wine?”

He extended his hospitality to the merchant, who took the cup and said, “Yes, maybe chase away the fever ~ and if the good Lord allows it, even Death itself.” He raised a toast to Blasi and guzzled half of the goblet.

“Argh!” The merchant growled, wine running down his beard. Blasi smelled of his own goblet and sipped from it. “’Tis bitter,” Blasi complained, smacking his lips. “How long had the wine been open to the heat of day?”

“Since, Avignon. After hearing news of the pestilence’s arrival in Avignon, I made haste to load the cart. I forgot to cover the cask.” The man wiped his lips against his sleeve.

“The sun killed it,” Blasi concluded.

The merchant choked down the remainder of his goblet, leaned toward the table, and refilled his cup. “Well, dying men do not drink to savor,” He stated as he fell back against the pillows and toasted the cardinal again.

Blasi raised his goblet, swallowing the last of the wine with a stiff face. “Nor do the dead,” he groaned. He too dipped his goblet into the washbowl for refill.

“You do not truly gather yourself to be dead, do you?” The merchant questioned him, chuckling. He looked up to discover a rather stern stare ~ an expression quite sincere. His grin melted and in that moment, perhaps Labatut might have seen a seed of madness, since sown in the priest now standing over him. The merchant tore away his gaze and watched the black window. Then he mumbled with raised brow, “Well, I certainly hope to be as dead as you in the end; I do admit.” He toasted in the priest’s direction and washed down another cup. Then he dipped his goblet back in the wine bowl. He groaned. “My condition worsens.” He wiped sweat and snuggled deeply into the pillows, nursing his goblet with two hands and a smile, maybe, as would an eager child anticipating some bedtime story. “So, tell me of this army that you secured and what I would not believe of it. Oh, and of your leg wounds, if you might be so kind.”

Blasi turned and paced the room, passing the foot~board of the bed and stepping the paper flower flat. Yet, his eyes peered through the floor and into his past. “Well, I gather it matters not, now. ‘Tis not so sacred a secret that a dead man can not confess to a dying man.” He paced a bit more, in deep reflection.

The merchant barked, “Well, go on then! Lest this dying merchant finds himself dead even before the dead cardinal confesses!” Blasi spun about. They eyed one another and chuckled.

“Very well,” Blasi said, “It first commenced in Avignon ~ in the Chateau Rouge, where I stirred to a most astonishing spectacle.” Blasi paced the room with his goblet, keeping a fixed eye on the merchant as he shared an account of his intimate conversation with the specter of his dead brother ~ of his reluctance to murder a fellow Cardinal in order to extract incredible secrets from the Holy See ~ of his clever deception to steal heavily guarded pages that described the workings of doorways to Hell, itself ~ of his masterful orchestration of a conspiracy against an unsuspecting pope that earned him the keep of a king’s army ~ of his unprecedented siege of a fortified abbey, with little loss of life ~ of his freeing demons that were to destroy all of England’s armies ~ and, of the ultimate unraveling of his plans via the imprudence of a brash and reprehensible captain. Occasionally, the merchant moved to speak, yet Blasi commanded his attention with the same fiery flare of incessant oration as did he, when serving as the superlative speaker that oftentimes dominated the floor of the College of Cardinals. And through all of it, Blasi refilled both of their cups until they consumed all of the wine in the washbowl.

Labatut considered the origin of his now heightened concern and found the culprit. Miniscule as it was, yet, nevertheless evident to him, a new and unnatural glimmer stemmed from out of the cardinal’s gaze ~ a peculiar gleam that he had not initially noticed. It seemed that Blasi watched him from two unlike directions, with a good eye peering over his shoulder and a bad eye staring completely into his soul. He felt the white eye to be looking inside him, and everywhere at once.

Blasi briefly left the room with the empty washbowl only to return with an ornate three~legged pitcher that brimmed with wine. Even as he placed it atop the end table, the merchant quickly withdrew and leaned stiffly away from him. Blasi pretended not to notice, as he was particularly engrossed with the task of refilling and inspecting the sick man’s cup, and with such care as to perhaps suggest that the wine was a precisely measured dose of medicine. “A bit more of it should lessen those now more manifest expressions of your infirmity,” Blasi claimed with the confidence of a practiced physician. He extended the full goblet and a cajoling smile to his seemingly bed~ridden patient. Yet, the merchant only stared at him. “Take the cup,” Blasi insisted, “Drink from it. Drown your affliction.” Yet, the merchant’s eyes darted about the room as if to search for hasty escape. In the dim glow of the candelabrum, Blasi saw the trailing beads of sweat roll down the man’s brow. “Your illness has you with a fever. Collect yourself and heed my word. I insist that you drink whilst you still have life enough to steady a cup.” Blasi leaned further over the bed. “Take it!” he barked, refusing to acknowledge the swelling circle of urine in his guest’s lap.

Wine sprayed as the merchant slapped the goblet from his hand. “Stay your distance ~ I drink no more with the likes of you!”

“As you wish,” Blasi calmly replied, straightening himself and wiping the spatter of wine from his clothes. He turned away and gave his attention to refilling his own cup. “Regrettably, I must continue to drink with the likes of myself; and soon enough, the mounting pains of your failing condition shall beg of you to do the same.” With a full cup, Blasi returned to his self~appointed station and stood beside the window, allowing the man ample space to gather his composure. Blasi nursed his cup, passing his time with outwardly irreverent speak and in a litany of abnormal introspection and ominous prophecy, unbecoming of even the least committed men of the cloth, especially a College Cardinal.

Blasi continued with only a murmur, his face pressed against the windowpane, him pretending to see keenly through the ink of night and study a steady stream of plague~infected passersby; “Look at them, altogether walking like a column of corpses. They are already dead ~ all of them. See how they struggle in their hopeless condition; driven only by fond memories and lasting daydreams.” He sighed deeply, savoring his memories before offering a rather uncommon connection in combination with foresight and hindsight; “At first light, we shall discover even more of them daydreaming along the roadside; with sated smiles, naked selves, and flies playing in their eyes. If they only knew the truth about themselves, then they would stop feigning life and fall still. Look at them, walking ~ pretending to live. Only in death shall they grasp the whole of their condition; that they were fools for trying to survive in a world where Death is weaved into the very fabric of its design. In the end, nothing of an earthly meaning shall remain sacred. And what greater good can survive hopes and dreams if all is lost to the likes of flies?”

“I do not believe that you are a priest,” the merchant grumbled. “Who are you?”

“Who am I?” Blasi chuckled. “If I tell you how it happened, then you shall know who I am. It all began, simple enough.” After a pause of silence, he cleared his throat and spoke; “When I was but a boy, I saw a spirited line of ants climbing up the side of a large tree even though its higher boughs were aflame by a recent stroke of lightning. As the column ascended the tree, the ants burned and fell to the ground. I brushed them from the bark, yet more followed the same course. I spit in their path, yet they crawled around the spittle and continued their upward march. I even smashed some of them, hoping that the others might instantly sense danger and turn about, however, they only crawled around the dead and continued their climb into the fire.” Blasi shook his head and chuckled. “In my boyish and quite foolish mission to save those ants from the flames, a falling limb broke my leg and nearly took my life. The moment moved the best of me, into my very soul’s core, even to alter the course of my destiny ~ from knight to~be, to me, as a bishop.” He snapped his fingers. “From a happening of ants, to a College Cardinal, you now know me for what I am.” Blasi turned away from the window and faced the merchant, preparing to present himself with opened arms ~ with a gesture of humble splendor. Instead, in a drunken stupor, he stumbled against the side table, sending its vase crashing to the floor. He dropped his goblet and fell backward, cracking the windowpane before steadying himself against the sill. His eyes lay fixed at his feet, where shards of a broken vase lay scattered amongst tattered paper flowers.

“Ants dying ~umph~ flies playing ~umph.” The merchant mocked and groaned as he sat on the side of the bed, pulling on his boots.

“You’ve no need for shoes,” Blasi stated, staggering toward him. “You must rest. What are you doing?”

“Stay yourself!” The merchant thrust a pointing finger at him and barked, “Keep your distance!”

Blasi froze, mid~stride. “Why must you re~dress?”

The man straightened his clothes. From beneath locks of sweaty and stringy hair, he kept an accusing eye fixed on Blasi as he growled, “To make right, what is wrong. I must take my leave from this manor of sin ~ and from this self~acclaimed, blasphemous spirit who worships himself as the venerable and eminent Cardinal Blasi!”

Blasi eyed the ornately painted porcelain pitcher, with a shiny surface of tiny blue flowers and its generous store of untouched wine. He asked, “And what shall come of our agreement?”

The man winced from the pain of his worsening condition. He brushed his hair back and looked squarely at the cardinal. “‘Tis yours ~ my wares; my cart; my steed ~ all of it. I need only myself for where I must go.”

Blasi now saw the man as a stranger ~ an utterly different person than that of the merchant whom he only recently met. The man seemed bruised and swollen, as if repeatedly beaten; and in the precise angles of candlelight, his markedly queer features glistened with an even sheen of sweat. Completely, his head appeared ape~like, with a grotesquely sunken face.

“Look at you,” Blasi exclaimed with a hint of expressed disgust, “You die as you speak! There is no other place of refuge. Rest yourself!”

The merchant nodded and staggered toward the door. “Rest assured that I shall ~ in peace, and without the company of Evil.” He departed the room, carefully making his way down the open staircase, sliding himself against the wall stones to support his step. Blasi trailed behind him, insisting that the man retire to bed. Yet the merchant ignored Blasi’s appeals and continued forth, mocking him with his every downward step; “The master of my house is Death! I am alive, yet I am dead! I conspire against His Holiness and the Church! I am a murderer of cardinals, abbots, and friars! I open the very gates of Hell! Let us go play with the flies in their eyes!”

“I said no such things!” Blasi barked. He pressed his chin to his chest and searched his clouded memory before asking, incredulously; “Did I say such?” He stopped on a stair and dangled his full goblet beside him, clumsily spattering wine on his clothes. “That we might play with flies?” He leaned a heavy head against the wall and snorted a chuckle. “Perhaps the wine has drowned my sensibilities. Please forgive me; I should do well to mind my tongue.” He then rushed after the merchant, who unabatedly continued forward, and clutched his arm. “No! I shall say nothing more. Come; you must return to the room!”

The merchant tore himself away from Blasi’s staying hand, left the stairs, and plowed through the kitchen before steadying himself against the stone hearth. He searched his whereabouts and found his belongings, highly stacked and covering most of the room. Across the way, a burning oil lamp sat atop his wine cask and its flicking flame cast the cluttered space into eerie relief. He stared at floating floor shadows as he chastised Blasi with indirect accusation; “And your legs are now healed when most men would die from such injuries. How could it be, unless ~ ah; yes ~ because heaven wished well upon you!”

The man stumbled to the floor and quickly crawled through the shadows ~ through many twists and turns, in a self~constructed maze of his own wares. Darkness swallowed him, leaving only his voice to call out, “Saint Denis, cover my way! Cover me!”

Blasi called out in the direction of the merchant’s voice, “From whom or what must he cover you? Collect yourself! The plague has made you gravely ill.” Blasi staggered after him, sloshing his wine. “Come back, I say!” Shadowy piles collapsed between themselves in a crescendo of contrasting tones as pots and pans clattered, and glass and porcelain shattered against the flagstones. “I see you there! Take hold of yourself! You’ve gone mad!”

The man leapt from a dark corner and wheeled about with a shovel, its blade only inches from Blasi’s face. The dim shine of its blade convinced Blasi to raise his hands ~ and his goblet. The merchant thrust the tool at the priest’s face, demonstrating a determination. “Shall I dig your grave this eve?”

“No need,” Blasi replied, surrendering ground. “Shall I not prepare yours, as you wished?”

“No need! Step away from me,” the merchant spat.

Blasi blinked and retreated a few steps before wiping spittle from beneath his eye. “As you wish, Monsignor Labatut. I mean you no ill will.”

“In league with the Devil and guised as a priest, you are,” the merchant growled, jabbing the blade at Blasi and driving him backward, through scattered heaps of clutter.

Blasi stumbled over the miscellany, yet managed to keep his goblet from spilling. The merchant hastily escaped the corner. He high~stepped through the debris, quickly forging a line to the backdoor of the chateau as he complained, “Keep all of it ~ every spilled spice; every broken spoon, and every bitter drop of wine! Yet this meager tool is mine!” In his backward glance, the whites of his wild eyes seemed to outshine even the lamplight.

“Oh, indeed!” Blasi agreed with the maddened merchant; “‘Tis yours; as you say! Take it.”

The man turned and froze where he stood. The two of them stared at one another long enough to appreciate the monotonous hum of summer’s eve crickets, and the stifling heat and lingering stench within the house.

Blasi drew a deep breath and broke the silence; “So, what do you intend to do with the shovel?” He stole a sip of wine, exchanging glances between the blade of the tool and the cutting stare of the man’s illness~induced insanity.

The merchant finally spewed an anxious chuckle. “No, monsignor; you are no man of God. A drowning dog would find more promise of heaven than, a man in a grave that you prepare for him! I see you as the worst of devils, concealing your forked tongue beneath a façade of godliness whilst you remain forever unchecked to weave your evil.”

“I am who I say,” Blasi stated. “I am the very Cardinal who assisted you in your former dealings.” He pointed to the wooden keg. “That very cask came from the Great Cellar of the Papal Palace, of which I served as its sole overseer.” He then tipped his goblet toward the merchant, as if to raise a toast to him. “Even bitter, I know this particular grape by its taste; ‘tis no ordinary sort. What is more, I know myself as a man of God and France; however ominous I might seem to the likes of plagued persons or ~ drowning dogs ~ as you are so keen to say. With that, my offer still stands true ~ that I shall inter you with every reverence, rite, and prayer that you would expect from any seasoned priest.”

The merchant looked over his scattered wares, apparently contemplating the offer, as if hearing of it afresh. He snapped an attention back to Blasi and presented the shovel more threateningly. “And?”

Through a faint shaft of light that broke the shadows and bathed the floor, Blasi detected a miniature horse amidst the scattered provisions ~ bits of the porcelain figurine lay strewn over the flagstones, since trampled underfoot. A small pale horse’s head lay beside the heel of the merchant’s boot. As did the merchant, Blasi turned about and inspected the same cluttered surroundings, apparently reorienting himself to a much larger picture as he mentally chewed over what he immediately gathered as an individual and seemingly enigmatic state of circular and satirical references. Quite uncanny, he mused, that the now broken horse was an earlier gift to his nephew, which he acquired in secret dealings of smuggled goods from Genoese ships and, which most likely came from the very merchant who stood before him. Likewise, the cask of now bitter wine undoubtedly came from the merchant’s past dealings with him, when Blasi routinely smuggled kegs from the stores of the papal palace cellar in exchange for rare imports, which he used for collegiate barter and political bribe ~ imports precisely like the broken Far Eastern porcelain figurine.

“And? What then? Out with it,” the merchant shouted, narrowing his eyes, as if to pressure Blasi into revealing the deliberately inconspicuous contractual details of a Faustian concoction or devil~drawn deal.

Blasi entertained the man’s inquisitor~like grandstanding with merely a weary smile and a stolid tone in his eventual reply; “And ~ I shall use those other words in your service. After all, how else shall you find heaven without my praying in the other words?”

“With devil~words and evil~speak? Ah! As I suspected,” the merchant exclaimed, thrusting the shovel toward the cardinal. Yet Blasi stood, unflinching; staring blankly at the broken horse; lost in the memory of a young lad who once flew faster than any angel ~ and perhaps with such vigor that a kindly wind took notice and swept him away from all of which the boy knew, as a world torn in the wake of a malevolent and ungodly ‘pestinense’.

Blasi bit his lip; he nodded dispassionately. “Alas, I must insist that you now take your leave of this manor and its grounds. You may take the tool in your hand and anything more that can carry with you; however, the steed and His Holiness’ cask of wine remain behind as tithes and chattels of the Holy See.”

“I need no steed! And you might drown yourself in the wine ~ spare us the misery of your contemptible and unpardonable self,” the man growled.

Blasi breathed sharply and jerked a high brow. “Without adieu, I trust that you shall find your way, yes?”

“Indeed, I shall,” the merchant grumbled, lowering the shovel. He backed himself toward the door and opened it from behind his back. A cool breeze bathed the room to reveal a gentle scent of rain. Crickets droned in the distance. “I’ve a grave to dig whilst I have the means. And make no attempt to follow me.” A flash in the night sky briefly showed him as but a silhouette to Blasi.

Blasi reassured the merchant. “Not to fret, Monsignor Labatut. I have resigned myself to remain here, consumed by my own wash of affairs.” He tilted his goblet and inspected the level of its emptiness. “To drown in them, even.”

He watched the merchant peel strands of sweat~laden hair from out of his face, straddle the shovel over his shoulder, and step into the night. Blasi followed him only to the door before leaning listlessly against the entryway. He swirled his goblet, raised a half~hearted toast in the direction of his departing guest, and winced as he drank the last swallows of tainted wine. He sighed as thunder rumbled.

Apparently, the merchant saw his gesture ~ he yelled back towards Blasi. “Oui! Salut, diable!” Nonetheless, Blasi only turned about and secured the backdoor, his mind free of all but a full washbowl and an empty bed, both of which he intended to use as perpetual indulgence.

Outside the chateau, the dying man staggered through ever~taller weeds, brushing away broken threads of spiders’ webs, tattered cocoons, and prickly briars, as he prayed to God, Jesus, Saint Christopher, and every other blessed martyr that might have an ear to hear his plea for guidance. With his back to the road, he set his site on the rear of the manor grounds and pressed forward on a self~appointed mission, stumbling toward the black horizon of an untouched forest ~ for him, death had now become a personal matter and a private moment, not to be shared with the likes of anyone but himself and God. Unfortunately, only lightening lit his way, the former glow of starlight now strained behind the cloudbank of an encroaching storm. And beneath the grumbling sky, a stroke of heavenly flashes revealed a pair of high~stepping, well~crafted, double~stitched, green boots, complete with cuff tassels and metal fasteners, all of which a swelling sea of dark weeds eventually drowned away.

‘Twas the first and the last time that Cardinal Blasi was fortunate to enjoy perhaps a long overdue face~to~face engagement with the once prominent merchant, Jean Baptiste Labatut; master broker of the finest Far East imports and handpicked wines that France had ever known.

~*~

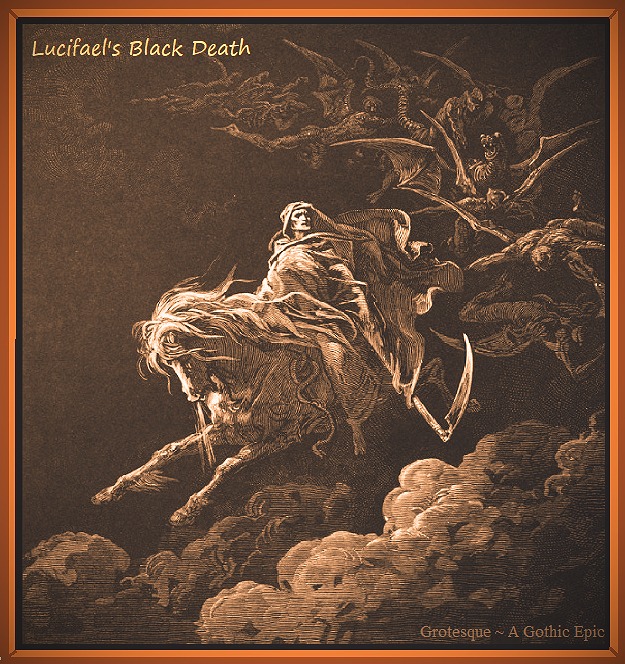

Death and destruction was all. The blackening infestation spread through every city and town in France, stilling their communal hearts with its destructive and unrelenting presence. Lowly peasants moved as riotous residents, razing entire villages to the ground, all the while, embracing a common nonsensical notion: that no evil would prevail in France as long as they were brazen enough to set its every city ablaze. Yet, the contagion moved within the unruly mobs like a wildfire, leaving them as black as the ashes of the buildings that they burned.

Desperate to shed light on the workings and origins of the Great Pestilence, in October of 1348, King Philip called upon the distinguished faculties of the University of Paris. Forthwith, an elected council of many disciplines convened, deliberated in ritual secrecy, and delivered their findings to Philip in a document called, the Treatise of the Paris Consilium. The collective effort sited several possible causes of the plague, including planetary alignments, underground vapors released from earthquakes, and poisonous particles carried on humid winds from decomposing marshes. Nevertheless, the commentary was merely a collection of speculation that did little to disclose a cause or cure. And although the Devil was not in the details of the document ~ even though Evil was absent from its canon of causes ~ the clinical exposition was an otherwise worthy attempt to address the apparently abrupt and enigmatic existence of this ever~consuming abomination. Hitherto, nearly ten million Europeans were far too engrossed with death to care about causes. After all, in the end, the dead remained dead ~ for the most part.

The Black Death was a raging hellfire, scorching the face of Europe and blistering Humanity, which was little more than a sapling in a fully blown firestorm. Like burning arms, the advancing lines of the Devil’s Disease reached further inland, stretching north and west to grasp untainted territories as it secured a stranglehold over the entire continent. One by one and end~to~end, countries curled like maps aflame.

Spain exploded, leaving a greater part of its cities exposed to a rather novel concept ~ dirtless graveyards. In the drought of an unyielding summer, the plague inundated its towns and, in the dizzying heat, its residents could not discern if they perspired from a summer heat or a sudden fever. Most of its inhabitants might have cast blame on the heat of the day, yet half could not easily discount the new black buds beneath their armpits as merely sweat or vapors. Indeed, the plague was a swift and indiscriminate executioner; the healthy retired to bed only to lay stiff by sunrise. And with Spain’s lingering drought and sweltering heat, cool clean water was liquid silver. Unfortunately, many of the communal wells lay contaminated with the remains of rotting neighbors. Some accused the Jews for defiling the water; and others charged the Muslims; yet oddly enough, with such an apocalyptic event squarely upon a populace of Christendom, only a handful blamed the Devil. Nevertheless, for those elderly residents who were too feeble to flee their homes and dared to consider even a single sip from the wells, the choice was as clear as the water they craved ~ indulge in disease or abstain in dehydration. Even so, in both despair and desperation, they drank from the cup, prayed deeply, and joined their neighbors in the cities’ dirtless graveyards.

Elsewhere, England’s towns and villages buckled alongside those of Spain. Even with stringent port regulations in place, the pestilence was a thief in the night, stealing its way through watercourses and sneaking passed the harbors of London and Bristol. Once aground, the contagion exploded. Physicians, priests, and politicians outwardly leapt into their graves; and like a sea of ulcerated lemmings, half of the cities’ populous followed suit. In the summer of 1349, the plague raced north, blotting the English countryside, carving its way through the congested cities of Norwich and Chester as it pressed forth into Wexford, Ireland. By the latter part of the year, the Black Death contaminated all of the region’s northernmost cities, including Edinburg, Scotland. With black rings around rosy lymph nodes ~ with pocketfuls of posies to chase away the decay, more than a third of Europe sneezed and fell dead.

Time rolled ‘round like the eyes of dying man and days followed themselves like the panting breaths of certain death. Men and women avoided the towns in search of food. Instead, they combed abandoned fields, hunted game in untouched forests, and searched mountain streams, desperate in their attempts to gather enough foodstuffs to survive the winter season. Families hid behind doors, which they marked red on the outside, and secured them within with stacks of heavy stones; farm tools propped against adjoining walls as weapons at the ready. And when winter ultimately arrived, many residents of central France were far too preoccupied with doors as probable points of entry, paying little heed to the certainty of their ceilings.

The Abbey's gatestone demons never made it to Cardinal Blasi’s intended destination ~ the French city of Calais and its English army of occupation. Instead, driven solely by the blackness of demonic possession, these flying chimera statues roamed the evening French skies, spreading outward with its equally spreading and blistering mist, and eventually reaching the edges of the village of Murat, where they crashed through thatch roofs as a bludgeoning of destruction.

The gravity of that, which crushed the village of Murat, could best be measured and appreciated by only a minority of the underworld minions; those elder and more seasoned demons of the treacherous realms of Tartarus and, of whom served as overseers within the Palace of Hades. Truly, they were allowed such liberties as to contrive many of the Hell’s more unmentionable agonies. These demons which possessed the grotesque statues of long~dead cathedral~mounted grotesques were merely the spiritual fabrications of Lucifael's damned legions. The stone figures were not driven by their former flesh and bone existence. They might easily be compared with nothing more than 'flying stones', inhabited by the spirits of demons who cast their wicked souls through the partially~compromised gatestone portal, with their real selves still imprisoned in Hell, as only two of the three gatestones comprising the Great Seal had since been 'unlocked'. Simply, as long as the Cancello Monastery gatestone remained closed, however weakened the Great Seal might have become, it still served its divine and intended purpose; and these underworld demons could only pester the world in the form of spirits of possession, specters, blue devils, incubi, succubi and the wicked like. And of all the incubi and succubi since cast into Hell ~ and there were many ~ Lucifael reigned as queen of the succubi, being the chief tormentor and spiritual fornicator, casting her likeness and wicked desires onto the sleeping and defenseless Sons of Man, and leaving legions of conjured grotesque offspring, of earthly flesh~and~bone, in her wake ~ and like Lazarus and every other spawned grotesque; all of them, only to be slain by the dawning of first light.

Still, Hell was not sated. In the passing seasons of yet another hellish year, the plague draped over Central France like an ethereal pall. And in the darkest hours of its enduring presence, the abbey’s blistering mist and roaming stone grotesques claimed an ever~broadening expanse of infestation and devastation. It then happened, in late 1350, that every resident of the villages of Vic~sur~Cere and Saint~Flour witnessed the horrors of chimera~like demons that swarmed the night skies as a covering of crows. Villagers screamed and scattered; however, lasting expressions of terror, which one might have expected to be preserved on the remains of at least a single victim’s face, was notably absent from every dead inhabitant ~ none had a head ~ not one skull lay estranged from other scattered remains. And these mass mutilations went largely unspoken, if not by lack of live account then by communal indifference of death. After all, every city, town, and village was failing in its own way and the downwind stench of them only served to warn a migrant plague survivor to choose a path less traveled ~ to avoid all origins of foul odors.

Nevertheless, flesh and clothes continued to fall from bleached bones, marking the passing days of one of Hell’s more clever designs. The Great Pestilence, which began in China with but a single bird, had managed to destroy a greater part of Humanity. Quickly as it came, it passed as settling ash on a dying wind. Like an overly swung sword or a wildly cast spell of evil, the plague’s wide swath of death cut through every vein of Europe before circling back into the heart of China. And when all the coins were gathered from the eyes of the dead ~ when the last ripples of the River Styx fell still, the plague had reduced twenty~four million European men, woman, and children to dirt. In China, thirty~five million souls vanished. Untold millions in the Indian and African landmasses were snatched from existence; all of them fell victim to Lucifael’s Black Apple Harvest. However, as dry numbers do not always move a mind to compare such mortal and historical proportions as adequately as perhaps a properly applied analogy ~ had all the European dead been stacked atop one another in a common grave, the depth of the plot would have exceeded thirty~six hundred miles. Even more, had all of China’s dead shared the same grave, its depth would have plunged nearly five thousand three hundred miles into the crust of the earth.

For Mankind, the Great Pestilence ran deeper than a six~foot pit ~ deeper than fathomless fear ~ it plunged all the way to Hell, from whence it was first concocted. And with all accounted casualties, half of the known world rolled over and died when a Taoist high priest and his captured grotesque of the Flying Dragon Temple, of the Three Great Gorges in Central China, dared to open the first of three seals to the Great Abyss. All of it happened in the darker pages of history, as unfortunate things invariably do.

Grotesque ~ A Gothic Epic © is legally and formally registered with the United States Copyright Office under title ©#TXu~1~008~517. All rights reserved 2026 by G. E. Graven. Website design and domain name owner: Susan Kelleher. Name not for resale or transfer. Strictly a humanitarian collaborative project. Although no profits are generated, current copyright prohibits duplication and redistribution. Grotesque, A Gothic Epic © is not public domain; however it is freely accessable through GothicNovel.Org (GNOrg). Access is granted only through this website for worldwide audience enjoyment. No rights available for publishing, distribution, AI representation, purchase, or transfer.